Within Sound: The Acoustic Sculptures of Michael Brewster (Capsule Review)

[Original publication: No Proscenium, 8/16/22]

Get Laura Hess’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

SubscribeSubscribe

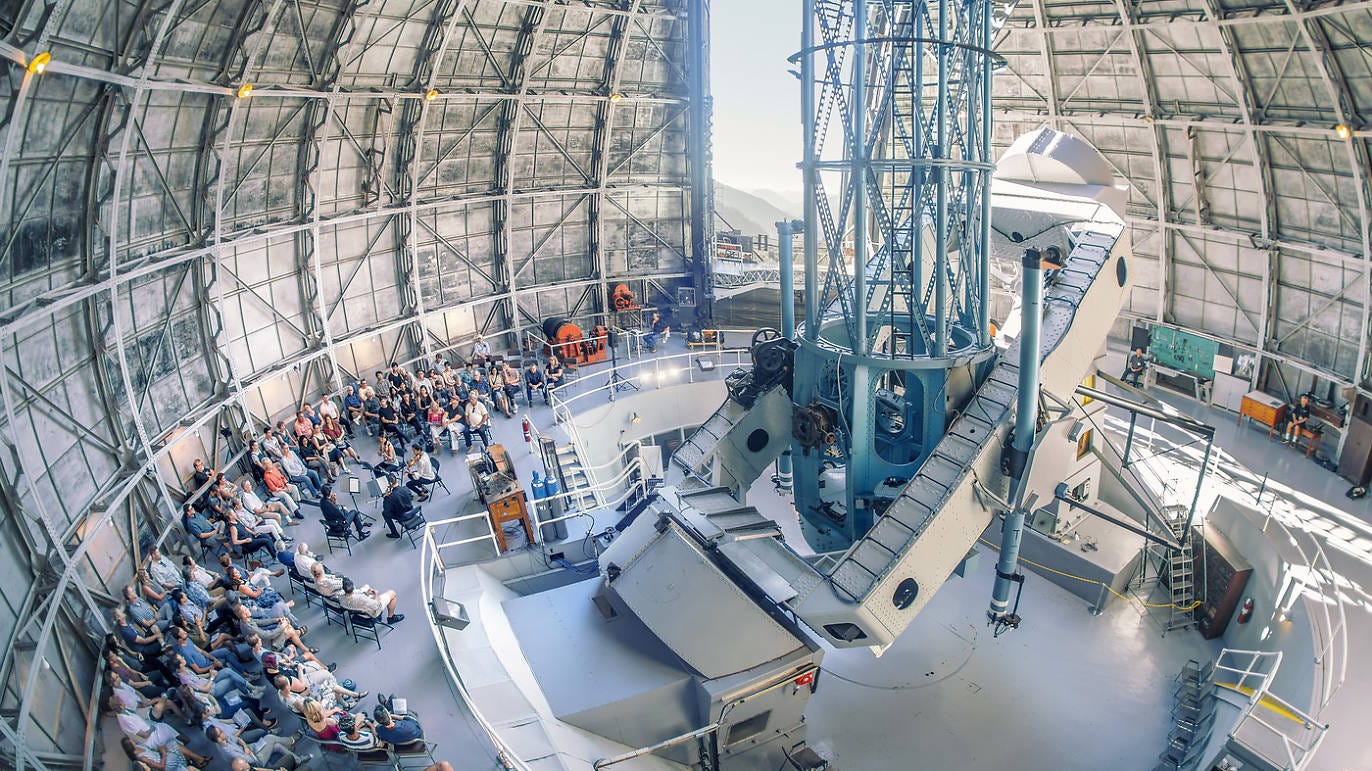

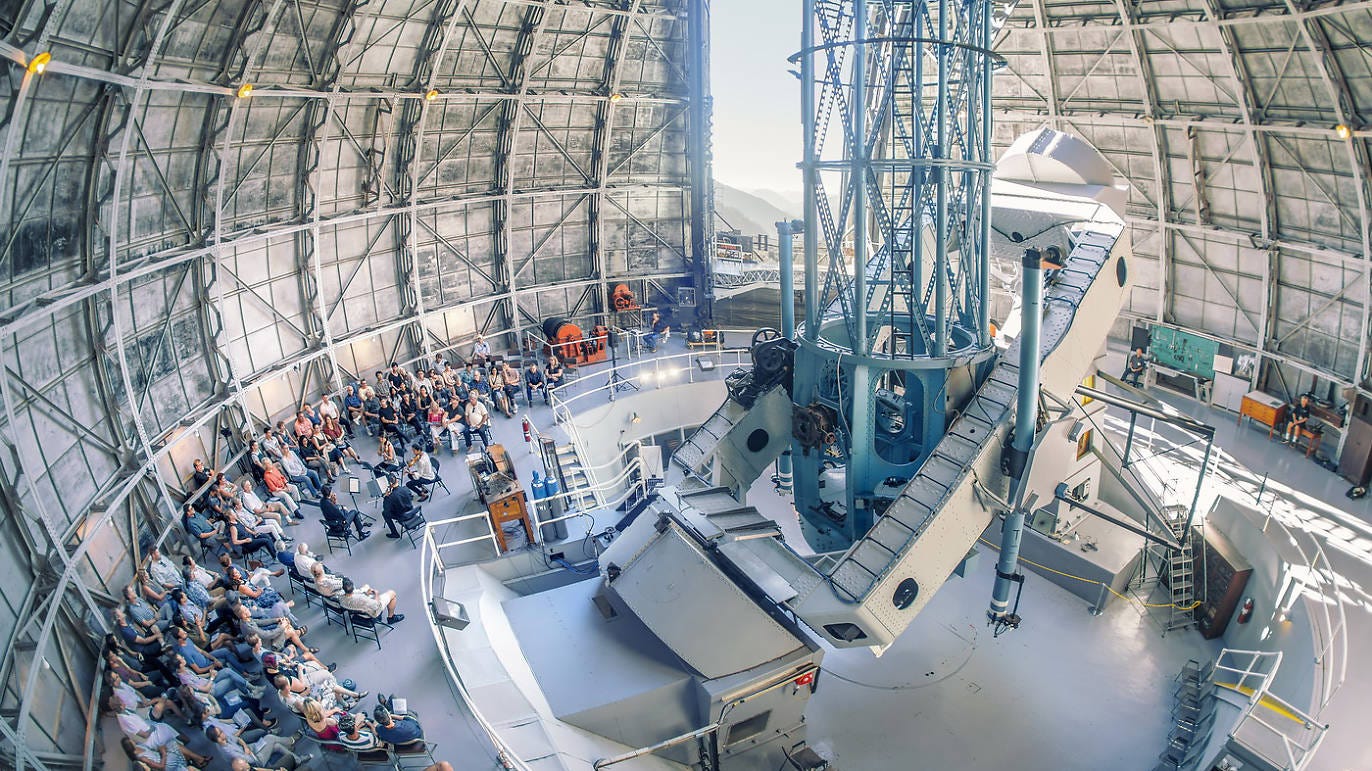

Near Pasadena, at more than 5,700 feet, sits the Mount Wilson Observatory. Its 60- and 100-inch astronomical telescopes are the two largest telescopes available for public use in the world. Last weekend, Within Sound: The Acoustic Sculptures of Michael Brewster launched the Observatory’s new “Arts @ the Observatory” program, a series of events at the intersection of science and art.

Brewster was a sound artist who designed immersive sonic environments starting in the late 1960s. Coining the terms “acoustic sculpture” and “sonic drawing,” he asked audiences to “look” with their ears. Consisting of six pieces presented inside the 100-inch dome (and its stunning acoustics), Within Sound was led by Homer Charles Arnold, a new media professor and archive manager for the Michael Brewster Trust, and supported by Alex Schetter, a sound art specialist and the Trust’s archival technician.

An interactive exploration, audiences could only experience the entirety of each sculpture by moving through the space. Brewster portrayed acoustic sculpture as “an inner as well as a visceral awareness that evokes sensations in mind and body.” This could not have been more true. Traversing the dome’s interior felt like moving through sound itself; the air seemed to have pockets of pressurized, tonal thickness. These “masses” had a complete shape: length, width, and even height. Crouching down, I sometimes crossed the threshold of a pocket’s outline and into a new cavity with a separate pitch, volume, and intensity. I also had sensorial responses, such as nausea, and trancelike moments. These reflexes were instinctive and immediate.

Placing “sight below sound,” Brewster reimagined auditory, spatial, and corporal interplay, while offering an inclusive experience for blind, low-vision, and sighted participants. At one point I arrived at the nexus of two sound waves, each set to a different frequency. By shifting my weight forward or back, I could “play” the waves, seemingly manipulating pitch and rhythm with my sway. I became listener, conductor, and instrument. Through Brewster’s magic I found myself Within Sound.