‘Ten Parcels’ and the Intimacy of Objects in the Time of Quarantine

Or, how a cursed camera and a 1916 deathbook reminded me of the power of the physical

It wasn’t the box, hand-addressed to me by someone from one of America’s most notorious supernatural stories. And it wasn’t the newspaper from 1916, or the turn-of-the-century folding camera that shockingly still opened. What took my breath away was a lock of hair from a child, fixed to a page noting her passing sometime in the 1910s. This is wrong. This is what spying on someone’s personal grief feels like, I thought. That’s incredible!

Okay, that may have come out wrong. Let me back up.

It started with a text from a friend: “If I nominated you for this, would you kill me?” The “this” turned out to be Ten Parcels, an alternate reality game that’s been quietly percolating since February. At first glance, it appears to be some sort of riff on The Magus, the John Fowles novel that described an ARG, The Game-esque experience called “The Godgame” back in 1965.

The main character that participants interact with in Ten Parcels is Maurice Conchis — the character that orchestrates events in The Magus — and he calls what he’s working on The Godgame as well. There are a few supporting characters, also using names from Fowles’ novel, and the general narrative thrust seems to be about uncovering the different, cyclical occurrences of The Godgame, how they ended in tragedy, and the larger meaning behind it all. There are also creepy, possessed dolls, tarot cards, and a general sense of dread and foreboding. Think of it as a disturbing, meta-playable version of Rabbits, and you’ll have the general idea.

The hook with Ten Parcels is that the story is delivered through ten different packages, sent out to various participants by Maurice. They are incredibly well-produced, featuring what appear to be authentic vintage items, disturbing imagery, and riddles and ciphers that are challenging enough to be engaging, but never going so far as to scare off a casual player. As for who’s really behind it, I have no idea — though Maurice claims we’ve met before. The result? A sense of mystique and danger I haven’t felt from an experience in quite some time.

Obviously, using physical objects in immersive or transmedia work isn’t novel. In large immersive productions, uncovering and interacting with bespoke props can be a fundamental part of the experience. Other productions, like Scout Expedition Company’s The Nest, use environmental design and materials as the sole mode of storytelling. That’s to say nothing of subscription mystery boxes that allow participants to sift through clues on a monthly basis, impersonal though they may feel.

When you think of tangible objects you can bring home, however, it’s often items from ambitious, old-school ARGs (raise your hand if you met up in 2007 for your Art Is Resistance recruitment gear), or mementos handed out from a brand activation or immersive production. The objective for the latter is obvious: people post the keepsake to social media, new people see it and attend said event, and the wheel keeps turning.

That’s not to condescend to the approach, either. I have a shelf of mementos from shows I’ve loved, and have done my share of tea-staining “vintage” items for productions; I was ecstatic every time I saw one posted. That said, they’re ultimately a value-add. The experience’s the thing, and whatever’s handed out after is simply a reminder of the time you had.

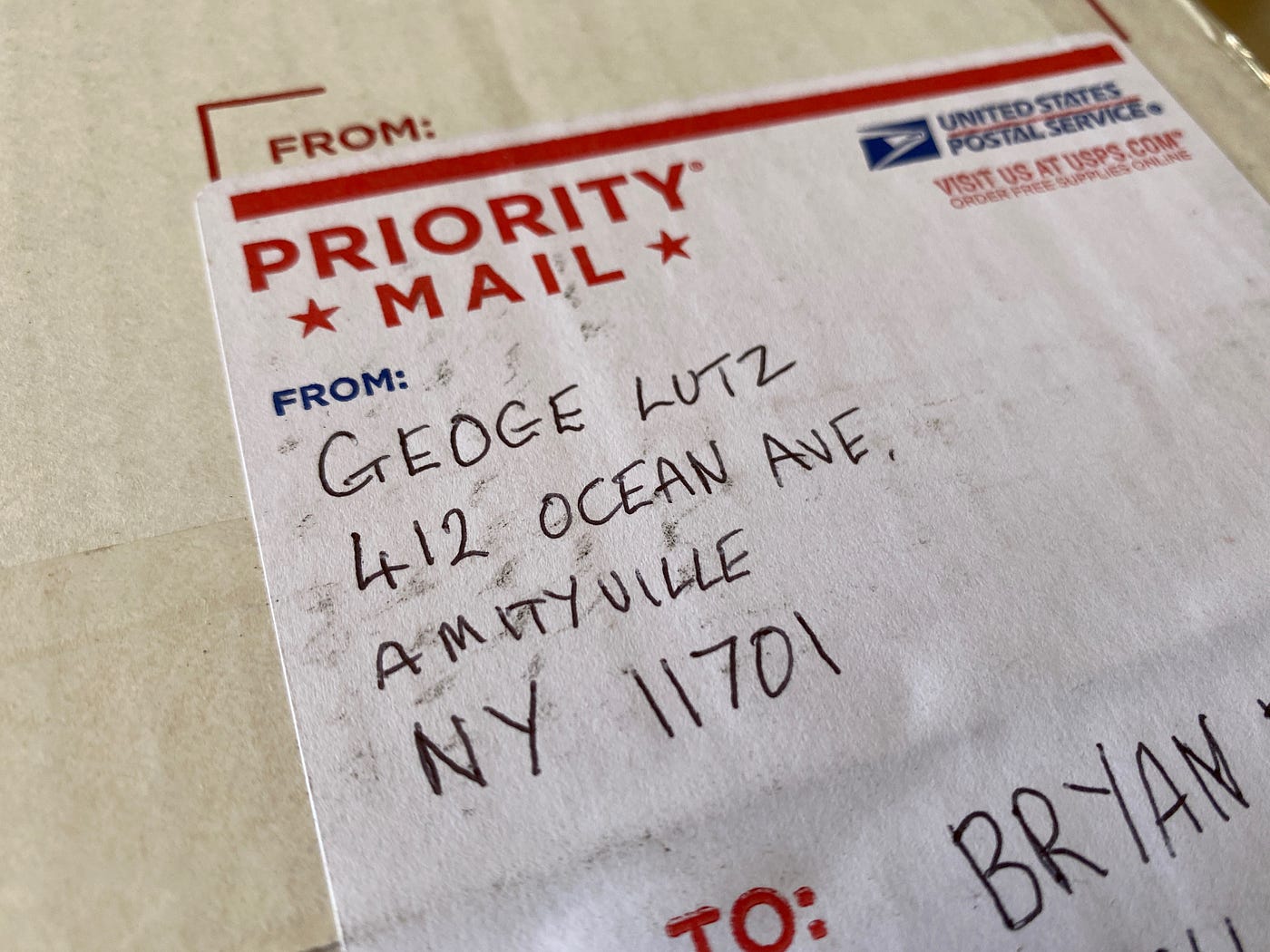

All of which is to say I didn’t quite know what I expected when the mysterious Mr. Conchis reached out to let me know he’d be sending me a parcel, taken from some far-off storage facility, and filled with notations from his father. When I got the tracking number, I saw it was sent from Amityville, New York. Given that other packages had been sent from Los Angeles and Philadelphia, this was impressive unto itself given our collective state of quarantine.

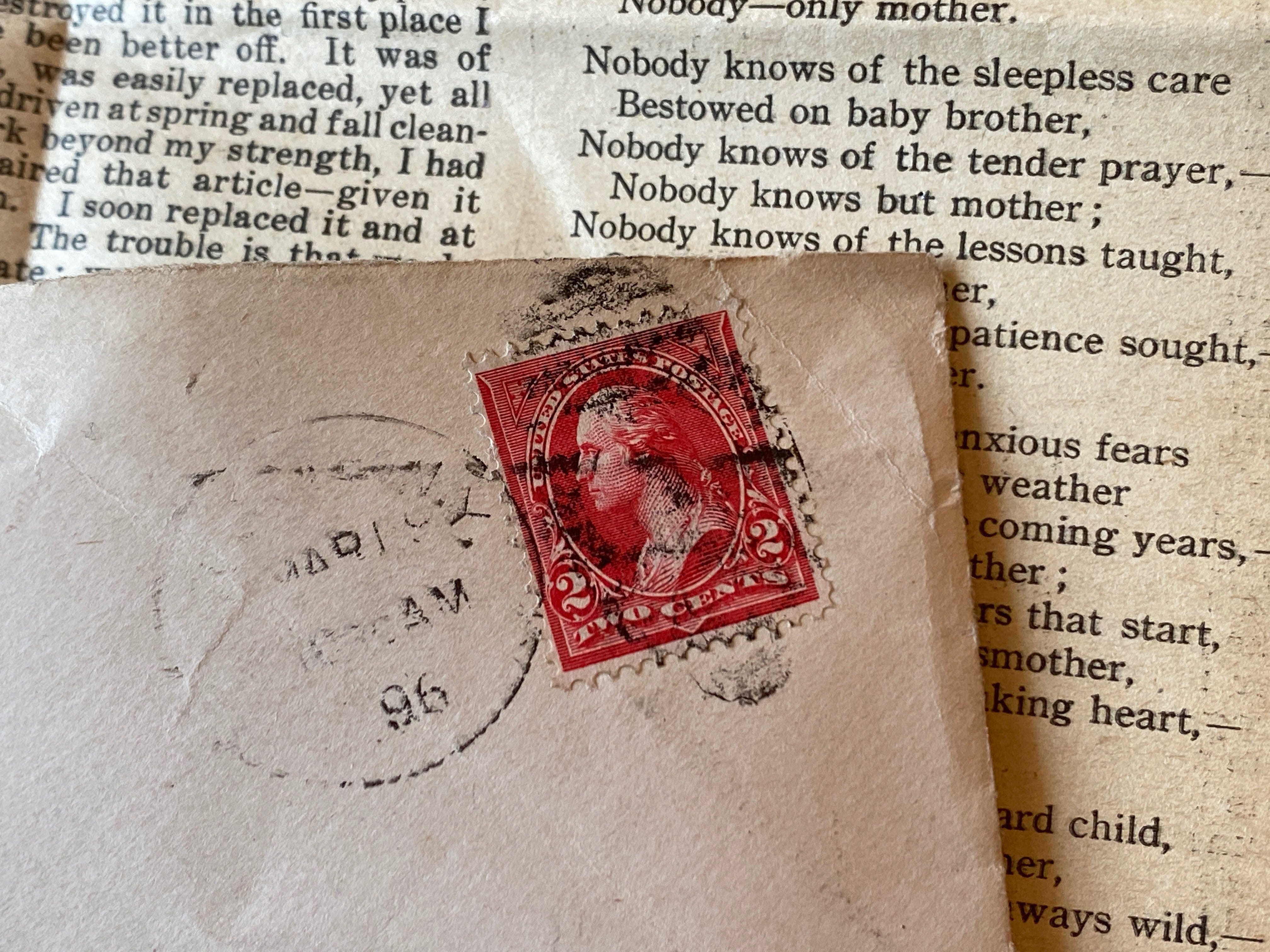

When I received the parcel the return address was “Geoge Lutz”, 412 Ocean Ave. George Lutz is the father from The Amityville Horror, but that address was the one used specifically in the 2005 movie remake, rather than the actual house address itself. Movie characters have ostensibly sent all of the parcels thus far, with one letter missing from each of their names.

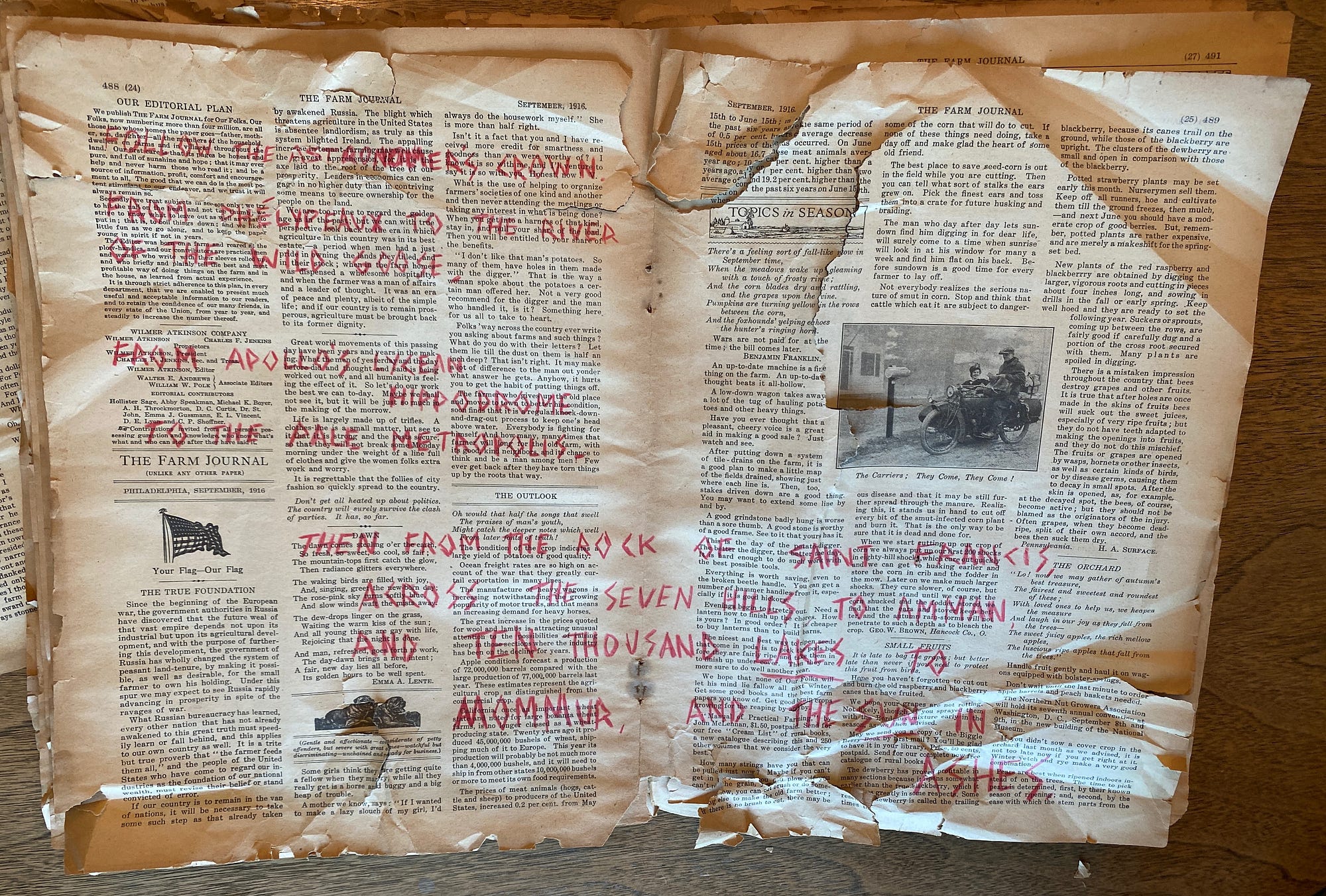

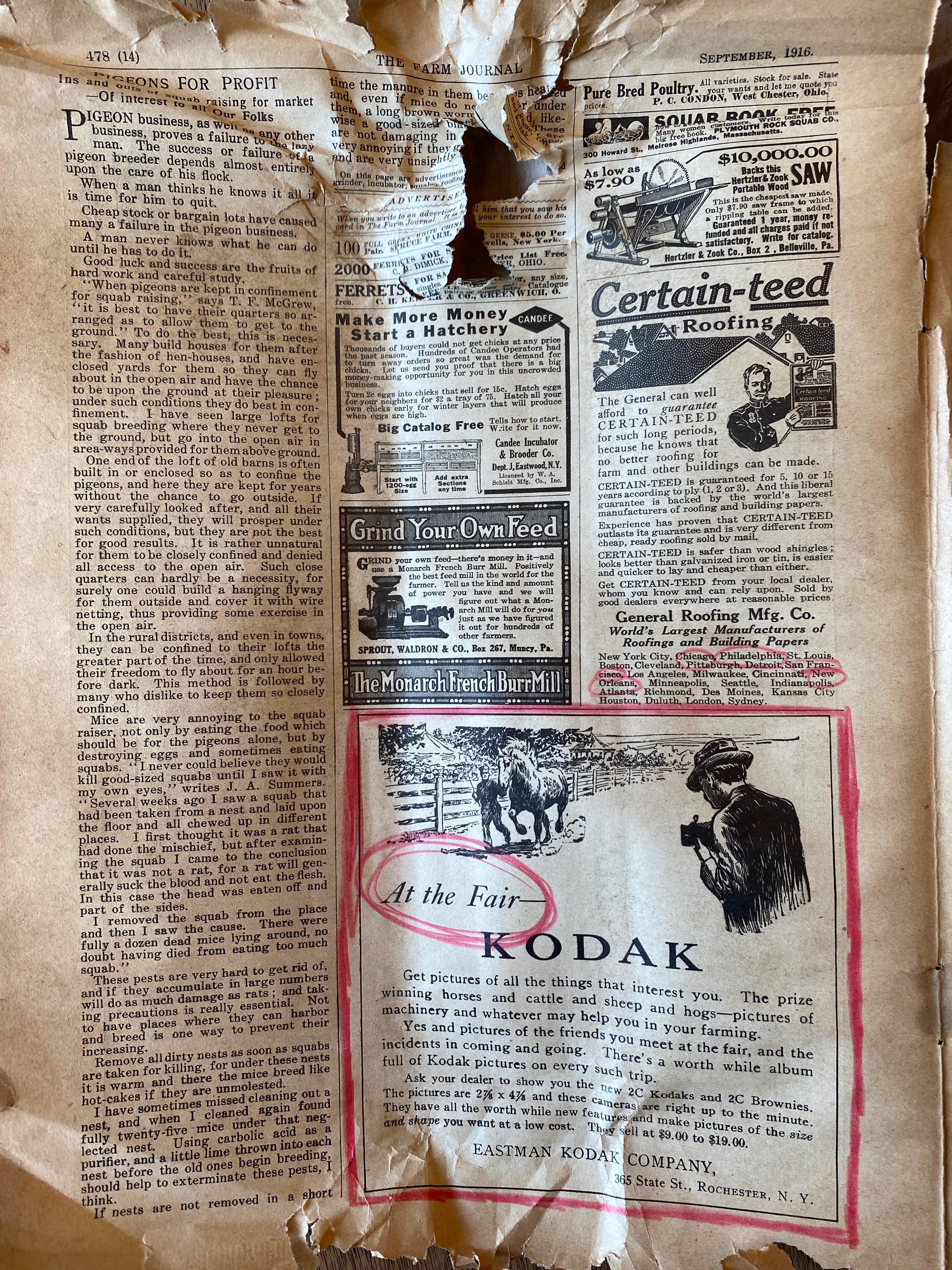

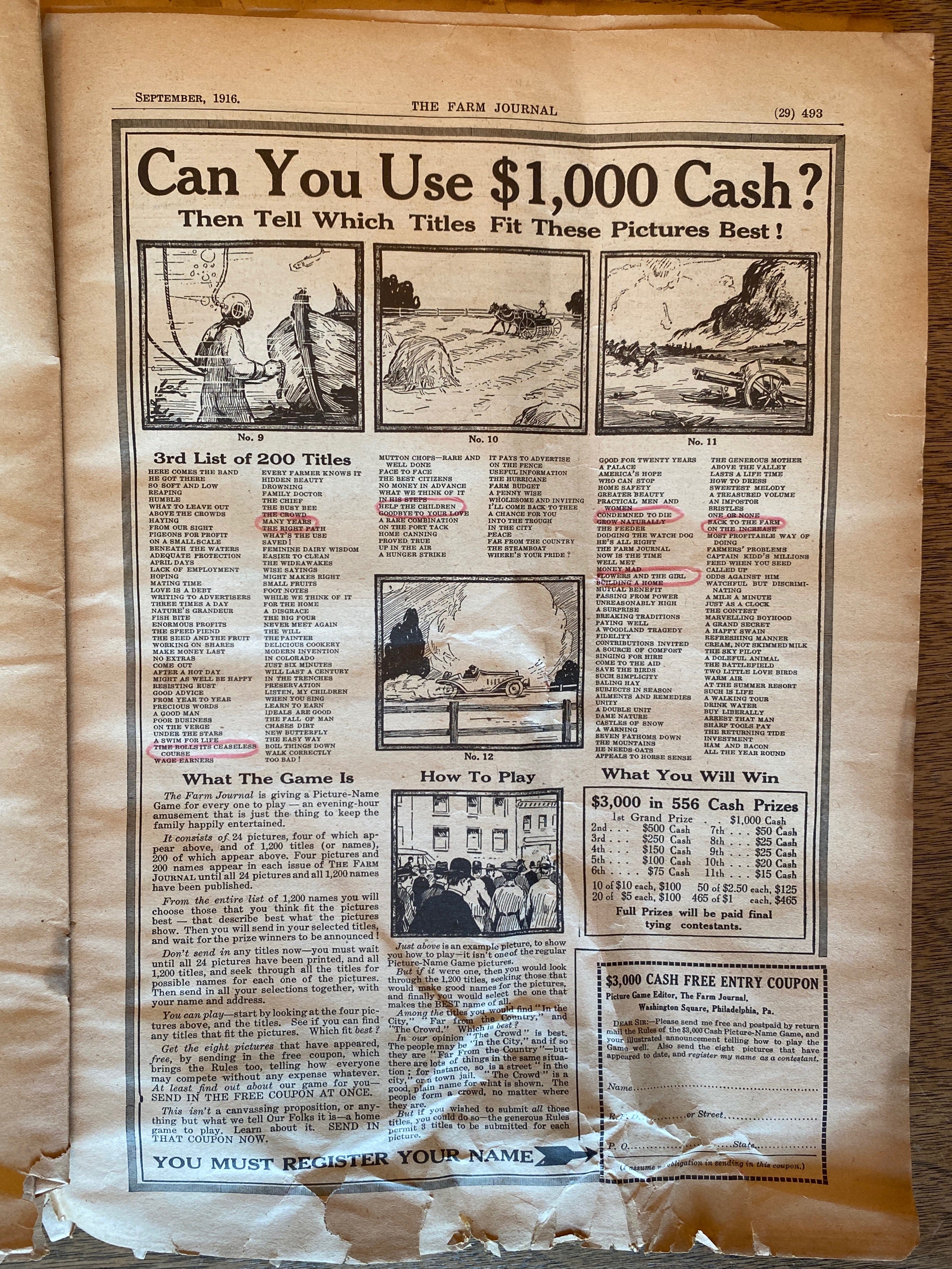

Inside the box was… well, it was surprising, even given the reputation the ARG has begun to build for its detail work. The parcel was stuffed with pages from the September 1916 edition of The Farm Journal (yes, the publication is a real thing, and judging from the look, feel, and smell of the pages, so were they). Various riddles and ciphers were scrawled across it, and I uncovered a vintage Eastman Kodak Model 3A folding camera, which judging from some internet sleuthing could have been manufactured as early as 1903.

I double-taked that, too. 1903.

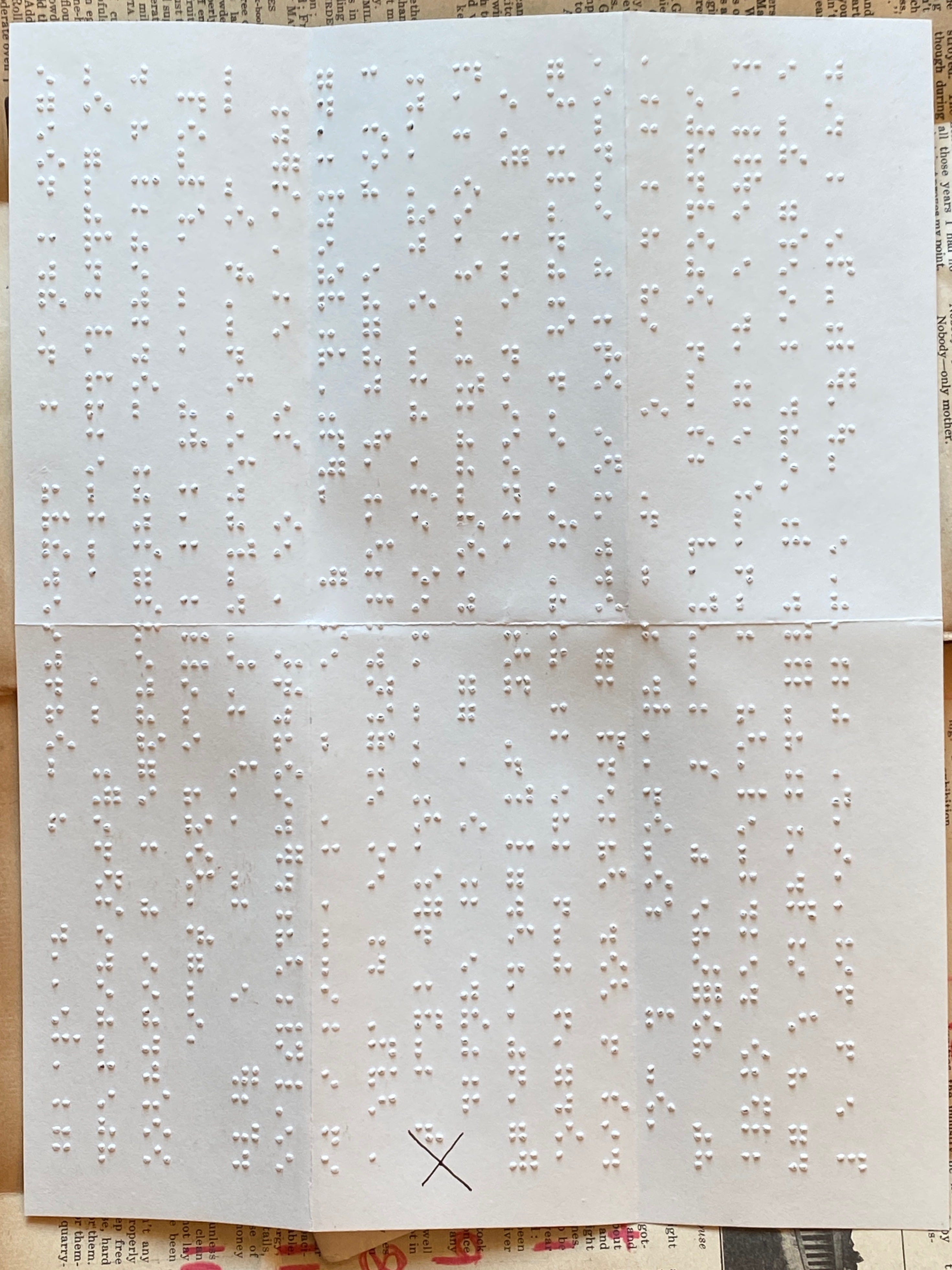

Clearly, whoever is behind Ten Parcels is executing it with an unnerving degree of detail and commitment. Hidden in the camera was a photo of a man, imprinted with a raised series of dots. I discovered that he was William Bell Wait, creator of a Braille competitor called New York Point that allowed me to read the raised dots (“I once was lost but now am found”). New York Point was also the key to decoding a letter included in the package, ostensibly written by a women in a deaf-mute asylum in the 1910s who had lost her husband in a fire, as was looking for someone to care of her daughters. The girls, it turns out, had three strange dolls that miraculously survived said fire.

It wasn’t just a collection of cool items or ephemera; it was a fragmented, interconnected narrative, all wrapped up in this one parcel. And that’s when I came upon the item that really upped the ante.

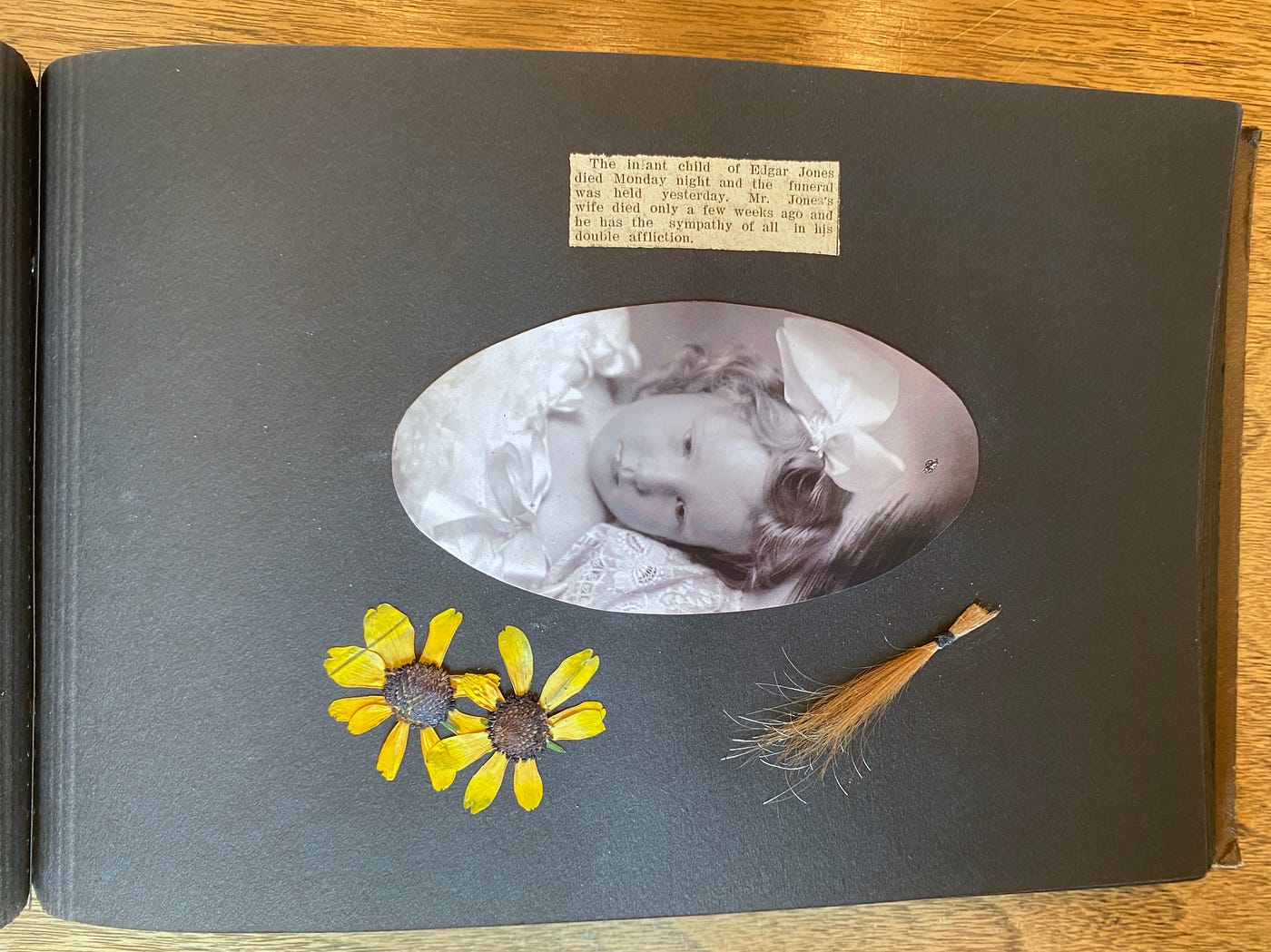

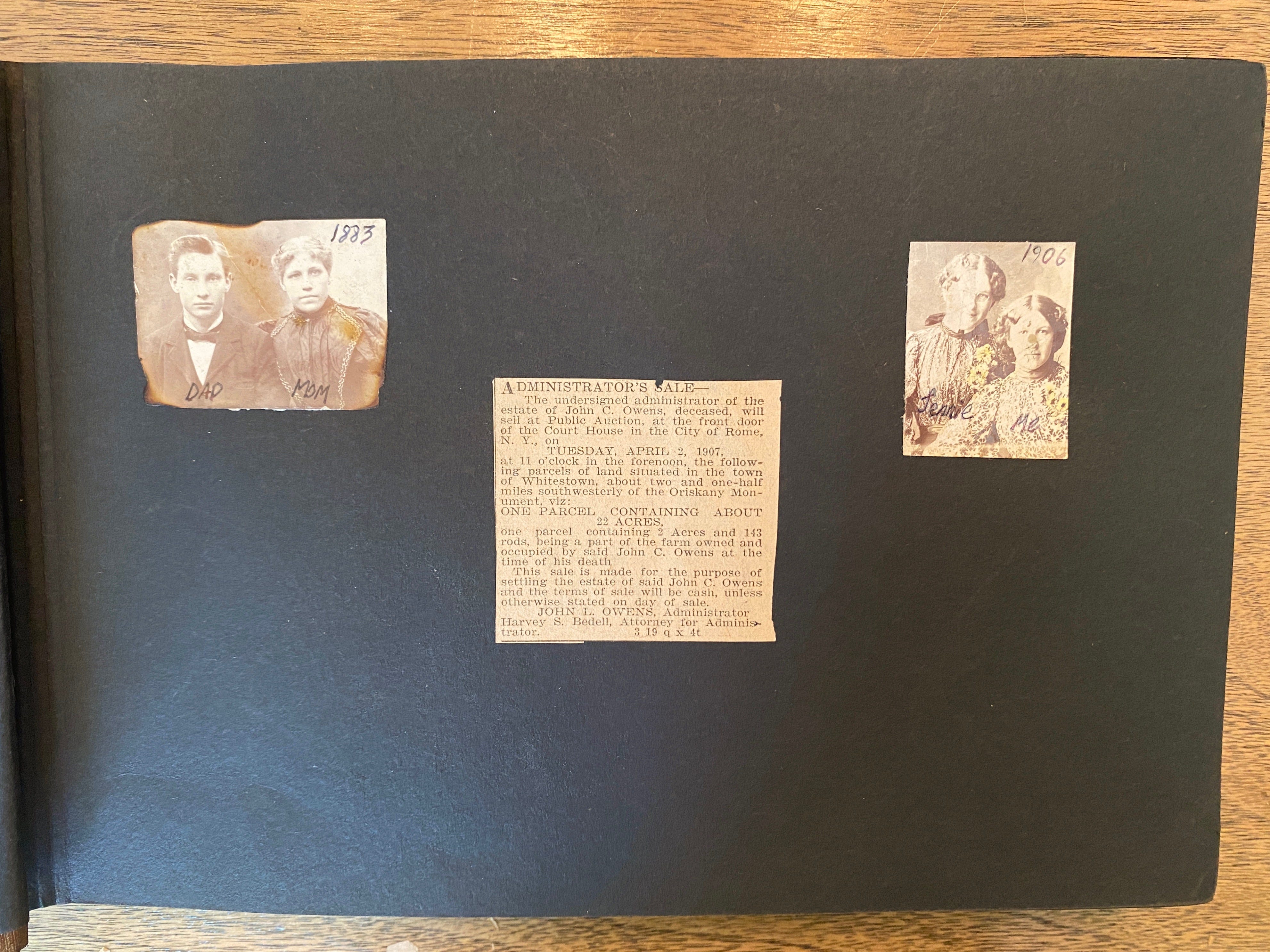

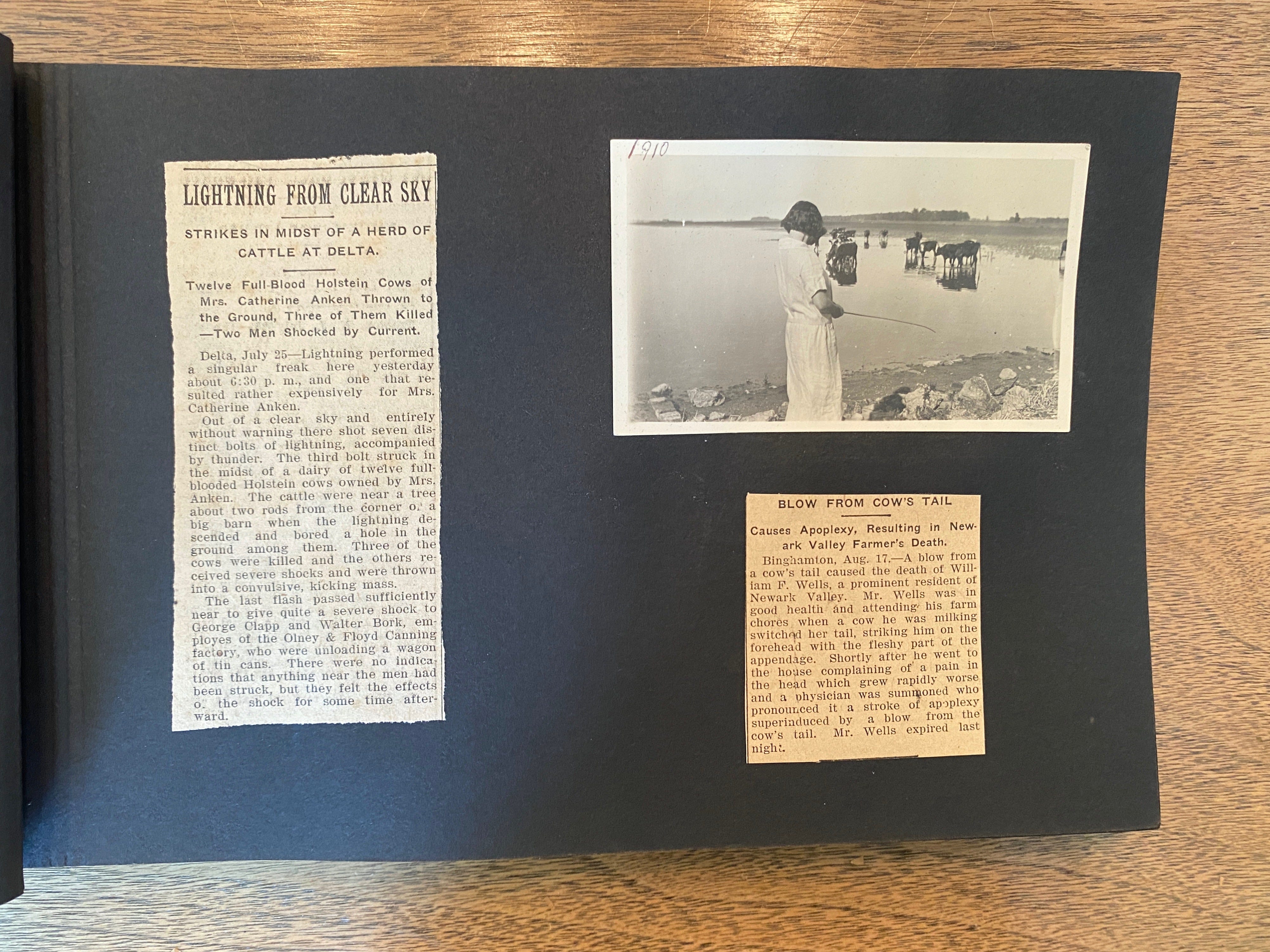

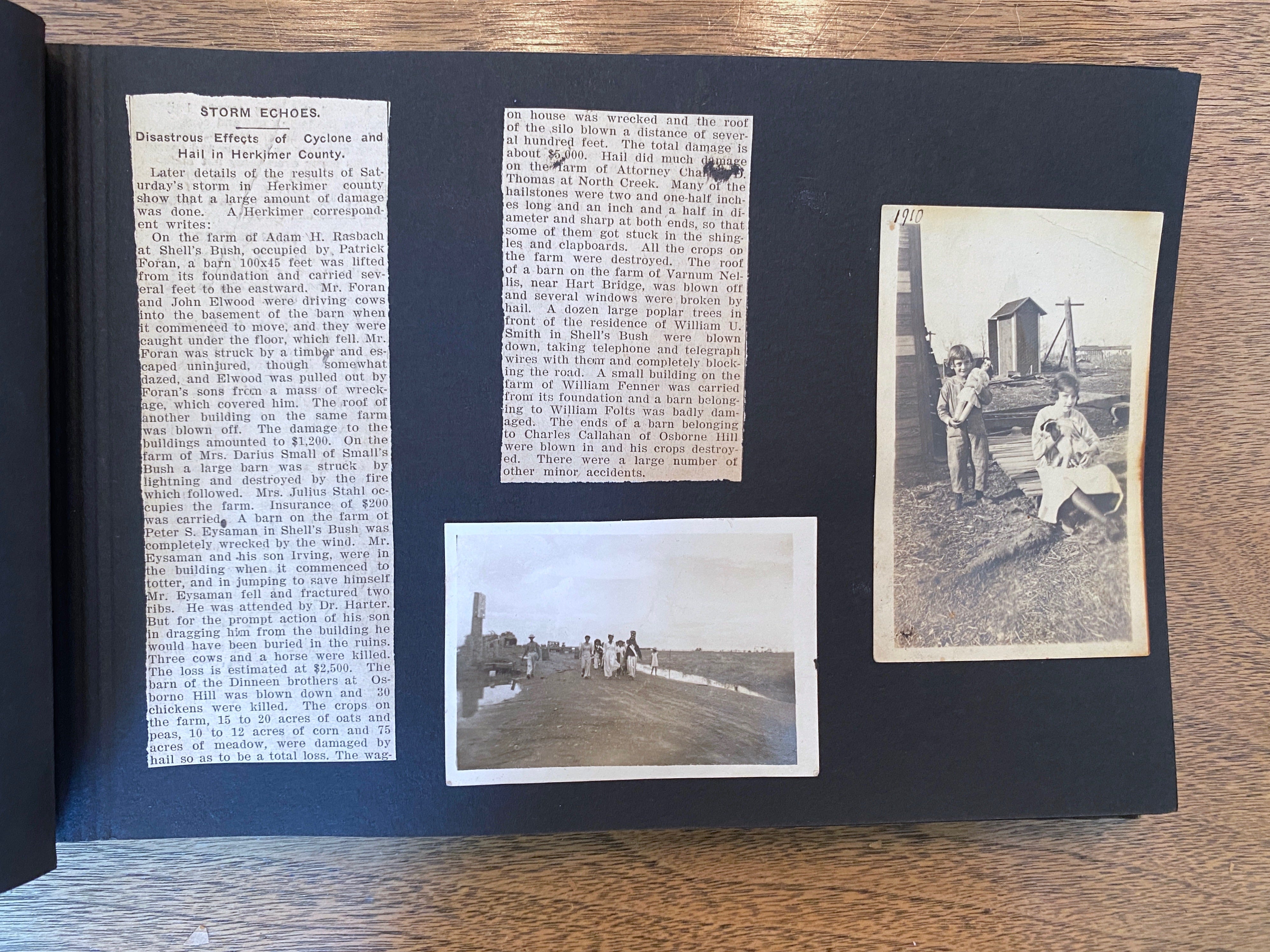

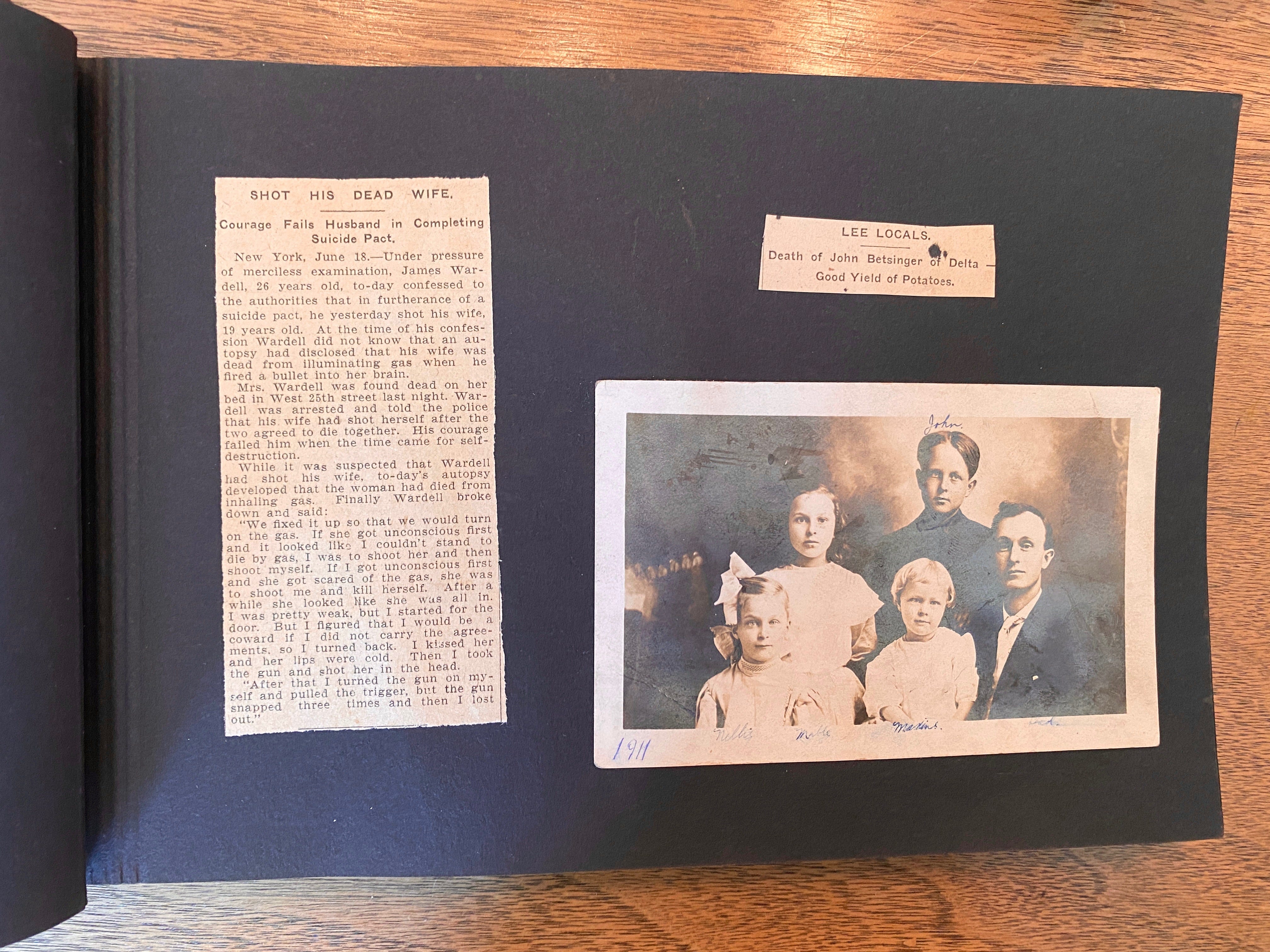

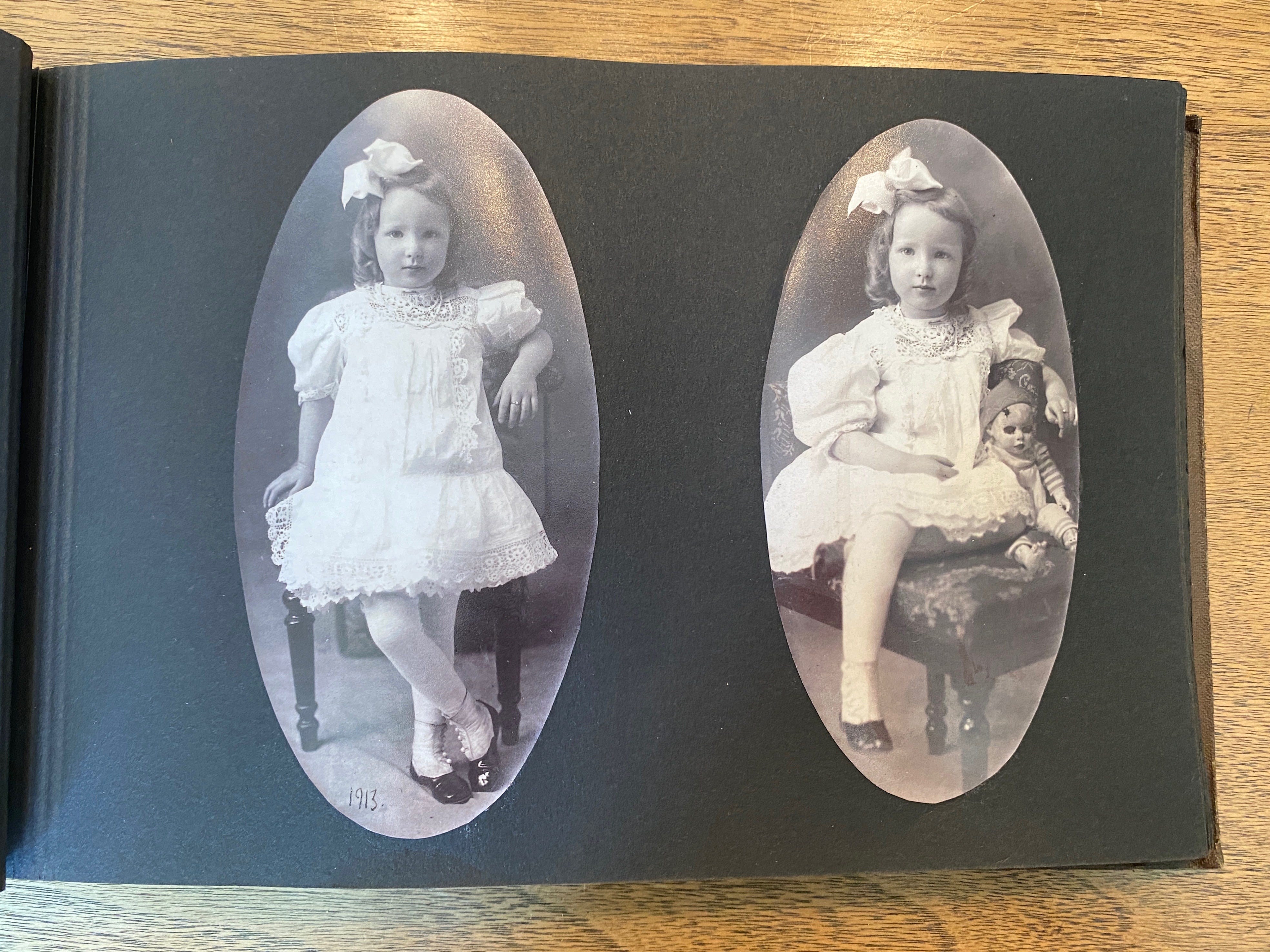

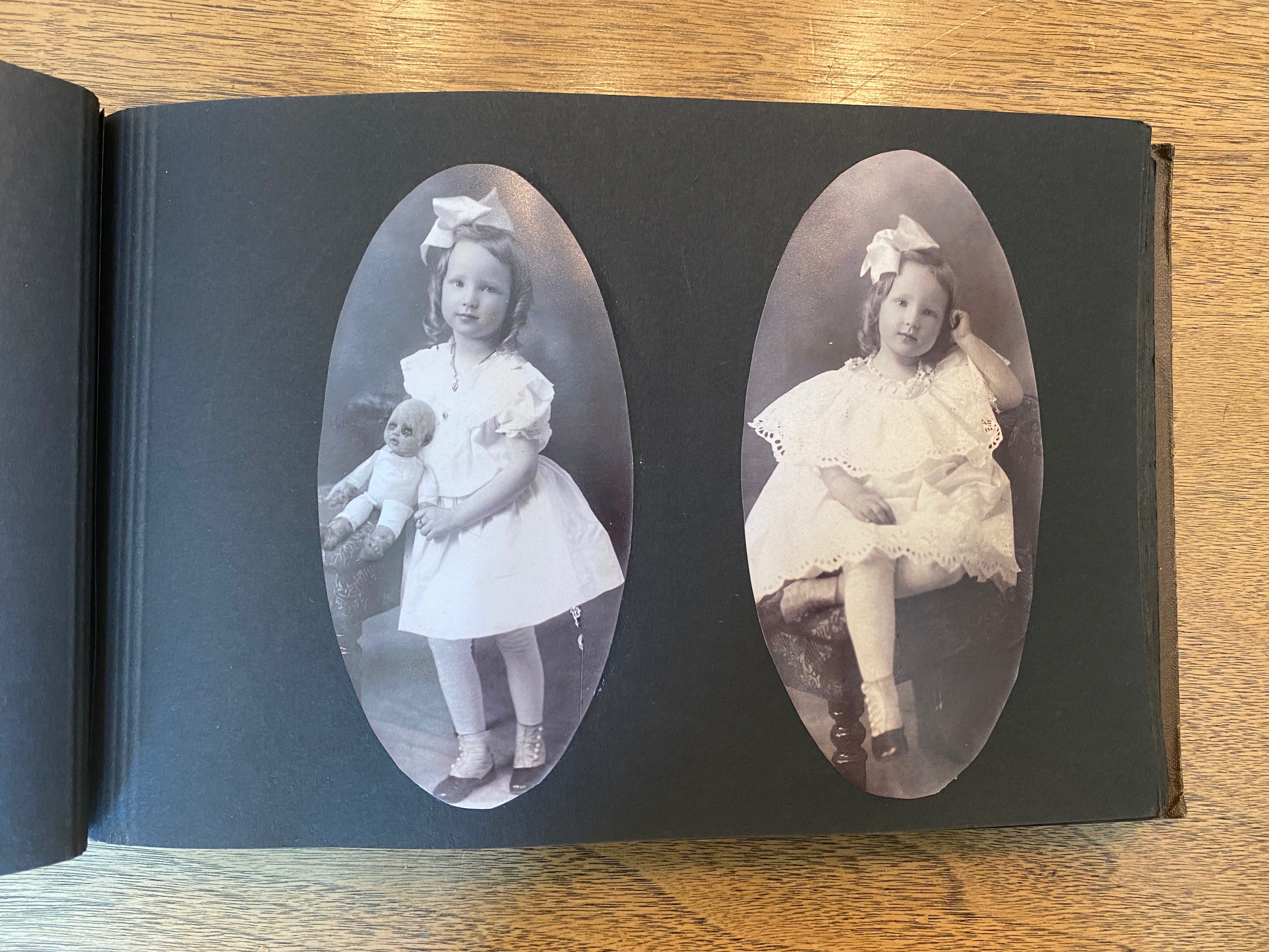

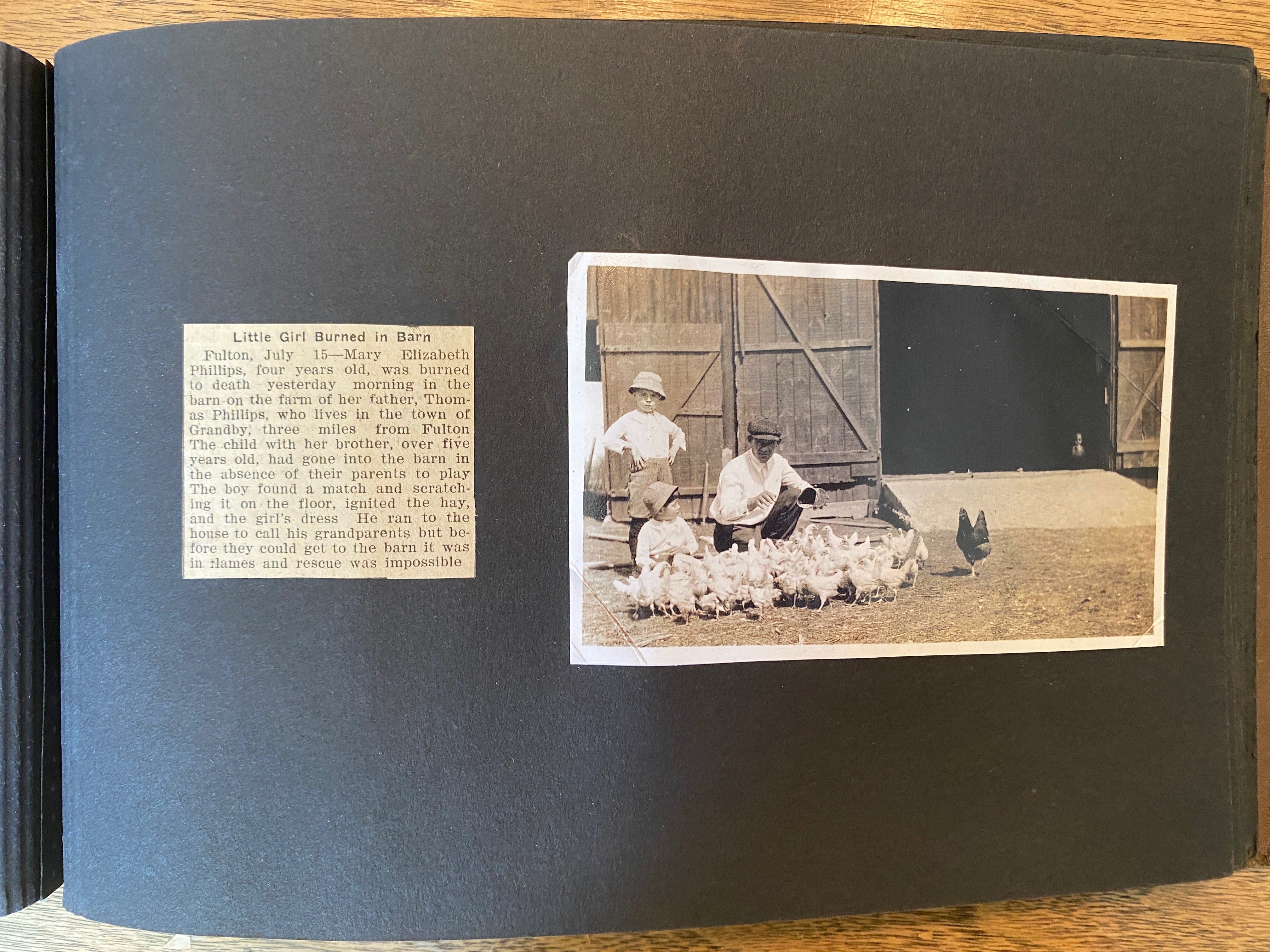

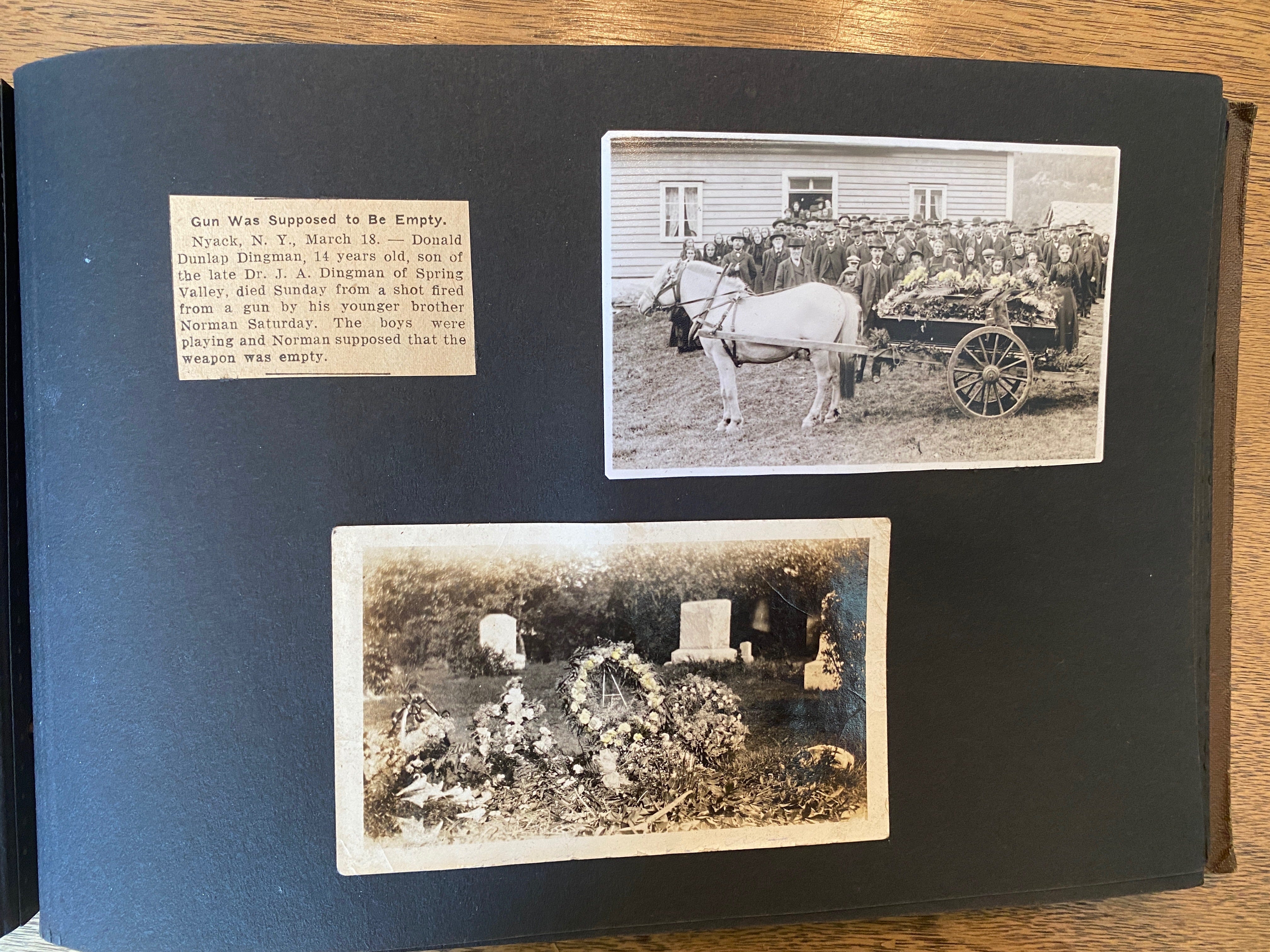

At the bottom of the package was a vintage photograph album, with forty pages of newspaper clippings and photographs that tracked a series of disturbing deaths, natural disasters, and fires from 1910 through 1916. Some of the images were almost certainly clever forgeries, with one of the nefarious dolls appearing in at least three of the pictures, but the rest appeared authentic, unnervingly realistic. It felt invasive; like I was looking into someone’s private materials. And then there was the matter of the little girl who died.

Based on the few previous pages, she may have been a twin, or just a young girl whose parents really went overboard on portraits. But the page that commemorated her death was arresting. A newspaper clipping explaining what happened; a pair of sunflowers pressed into the page; a lock of her hair. I recoiled — and was fascinated.

Was she one of the girls mentioned in the letter? Was this where the mother’s attempts to save her daughters ultimately ended? Did the demonic dolls have anything to do with it, or was the vintage camera — which I learned from the Ten Parcels community may be cursed itself — somehow responsible, dealing death to everyone if photographed? And who would have made something like this in the first place?

The questions didn’t stop swirling, but the lock of hair was the inflection point. A touch so subtle, genuine, and authentic it was heartbreaking to see. There I was, sitting in my well-lit dining room, having an entirely self-contained and incredibly disturbing immersive experience. There was a character I cared about, a hope for redemption, a tale of tragedy, and an unsolved mystery of potentially monstrous origins. And that was all without delving into the macro picture of Maurice, The Godgame, and everything else that could end up being part of this project.

It succeeded because it told a story. One I had to work for, to be sure, but one that did what all fascinating immersive work does: create a narrative that the audience can step inside, engage with, and in turn have their own emotional experience.

How to pull that off is something I’ve been thinking about a lot as we’ve been shut up in our homes in this unprecedented, global experiment in… waiting. A variety of immersive creators have launched new ARGs and online-only shows, using social platforms, Zoom performances, and good old-fashioned phone calls and emails. They’re all experiments, attempts at creating something that can provide escape from the chaos of the outside world, and we’re fortunate that so many are successful in various degrees.

But I personally have only been able to fall so deep, because at the end of the day I know there will be no pop-up event, no actual immersive production at the end of the rabbit hole. There will be no physicality, the coin of the realm in immersive, because that’s the one thing none of us are allowed to have right now.

The dynamic is similar to what we’re seeing as so many transition to working at home with Slack and Zoom. Yes, people can use these tools to virtually assemble for meetings and figure out how to get things done, but none of them effectively replicate the immediacy of being there in a room with a colleague, a co-worker, a friend — or a performer.

But objects can change that. There’s a strange, but very real intimacy to holding something that you know a creator, somewhere out there in the world, has crafted by hand. It’s something you can touch, explore, and even smell. A project like Ten Parcels creates a living world by placing its artifacts in your hands, giving you a sense of presence as you explore, agency as you decide how, or if, to connect the various pieces provided, and the ultimate gift of play as you engage in whatever way you see fit. As Maurice makes clear in his emails, the degree and style of participation is up to you.

Get Bryan Bishop’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

SubscribeSubscribe

There are five packages left to be doled out in Ten Parcels, and no doubt just as much story to be uncovered, deciphered, and parsed together by the collective group of players. But for me, it has already done its most important job. It cracked open a door into a world full of mystery and foreboding, of undiscovered entities and powerful forces. And it did it not by asking me to climb into an elaborate story world as the cost of entry, or force some kind of digital suspension of disbelief. It did it by bringing its story to my front door

It’s a lesson I hope to keep front of mind as we move through, and past, this awkward time. Sometimes it’s easy to think that the existing facets of a given medium, or type of art, are all there is; that we can sit back, look at theatre, VR, AR, parks, and escape rooms, and say we’ve all got this immersive thing figured out. But in my mind, immersive work is best defined by the way it allows an audience to step into and engage with a fictional world. That can take the form of any of the modes I just listed, or new ones that haven’t even been conceived of yet. It can include literal agency, the illusion of agency, or no agency at all. It can even take the form of a package sent by a character from a 2005 horror flick.

I just really hope that camera isn’t cursed.

Below are a few of the items from the fifth package of Ten Parcels. If you want to get really deep, feel free to peruse the Google Drive folders here and here.

For more of NoPro’s coverage of Ten Parcels check out Cara Mandel’s “Of Creepy Dolls and Creepypastas (An ARG Diary).”

NoPro is a labor of love made possible by our generous Patreon backers. Join them today!

In addition to the No Proscenium web site, our podcast, and our newsletters, you can find NoPro on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, in the Facebook community Everything Immersive, and on our Slack forum.

Office facilities provided by Thymele Arts, in Los Angeles, CA.