‘Temping’ Makes Riveting Drama of Workplace Desperation (Review)

The solo experience offers us an opportunity to confront mortality and capitalism

(The following review contains minor spoilers.)

No one plans on being a temp.

It’s just something that sort of happens. One day you’re a rosy-cheeked undergrad studying French literature, sprawled on a campus lawn reading Baudelaire, and then you blink and find yourself doing data entry for a tech startup, hoping that at the end of your six-week contract you’ll be offered a permanent, salaried position doing more data entry. Your hopes and dreams have been set aside for now — there are no jobs in French literature — because you’ve got rent to pay and a cat to feed. It just… happens.

Temping is an interactive, site-specific installation for a single audience member at a time that puts the player in the role of a temp; The Wild Project, an experimental art gallery in Manhattan’s East Village, doubles as the “office.” As the participant, I’m filling in for Sarah Jane Tully, a 53-year-old actuary for Harold, Adams, McNutt, and Joy, LLP, a “global professional services firm.” When I arrive at the appointment-only venue for my 7:30pm shift, I’m greeted virtually by Sandy Johnson, one of Sarah Jane’s coworkers, who ensures that I am wearing a mask (I am) and instructs me to take my temperature and don a pair of rubber gloves. I am also given a corporate jargon-riddled welcome packet that contains information about the company and a tip sheet on how to sit more ergonomically at Sarah Jane’s desk. After all, as the tip sheet says, “the infirm are a drain on company resources.”

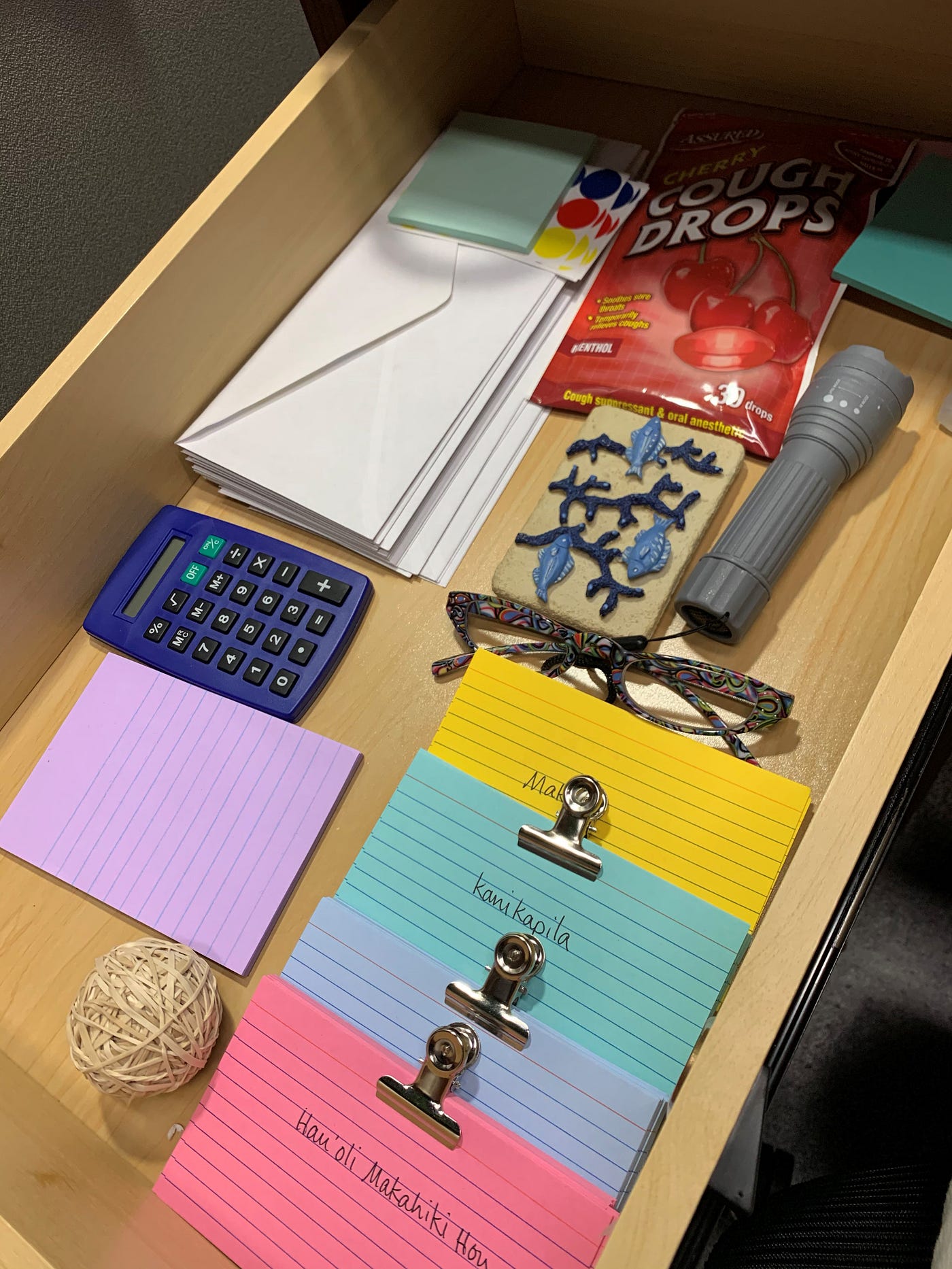

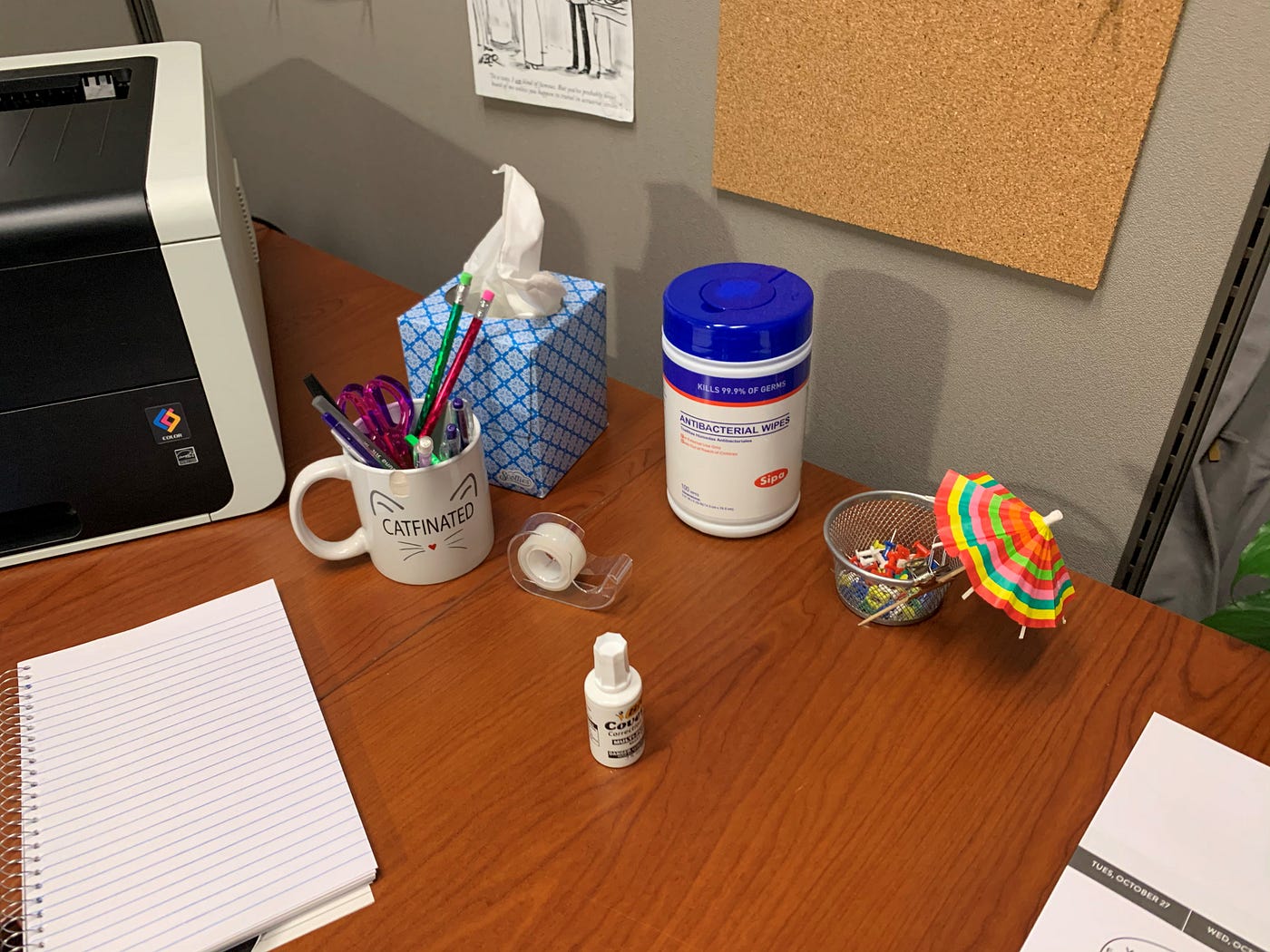

I am next given a key to Sarah Jane’s office and instructed to enter it and begin my shift. I take a moment to gather my thoughts and settle into Sarah Jane’s chair, her office, her life. Sarah Jane’s cubicle looks like many I’ve seen in offices across the city. A sensible grey cardigan is draped across the back of her chair. A pair of pink tennis shoes is tucked neatly under her desk. A chipped cat mug holds an assortment of pens and pencils. Cartoons clipped from newspapers featuring jokes about actuaries are pinned to her cork board.

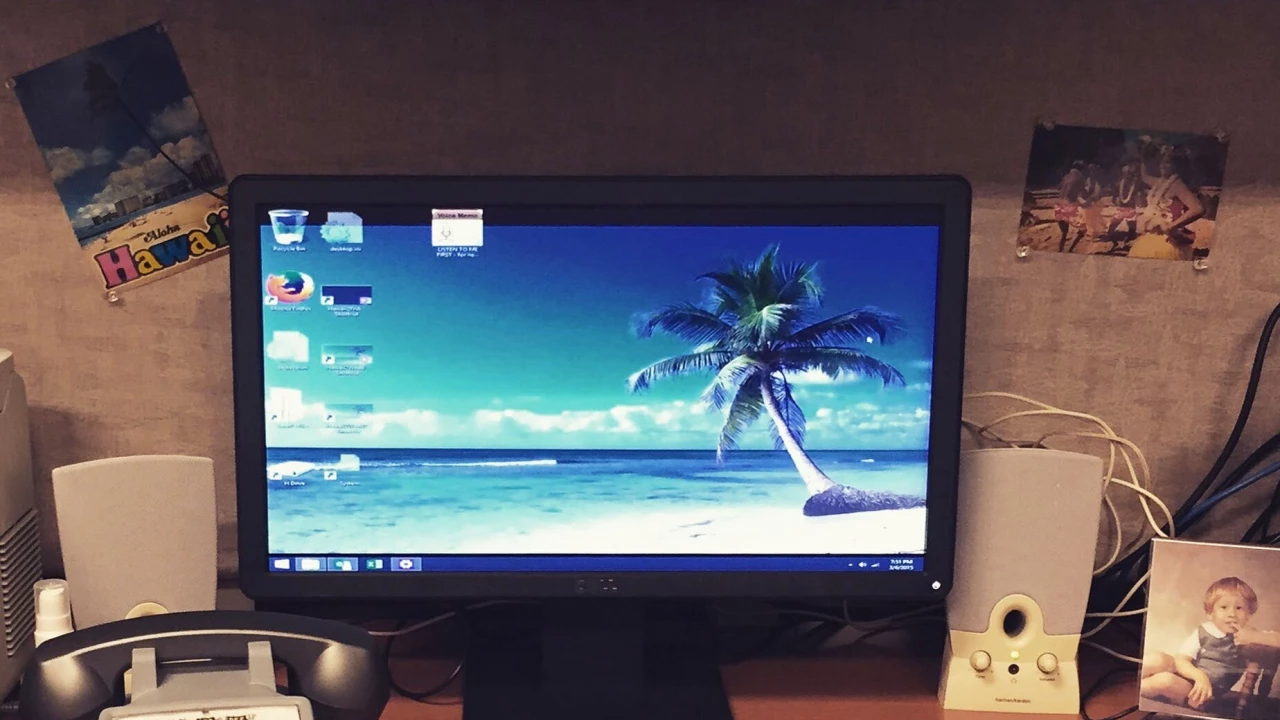

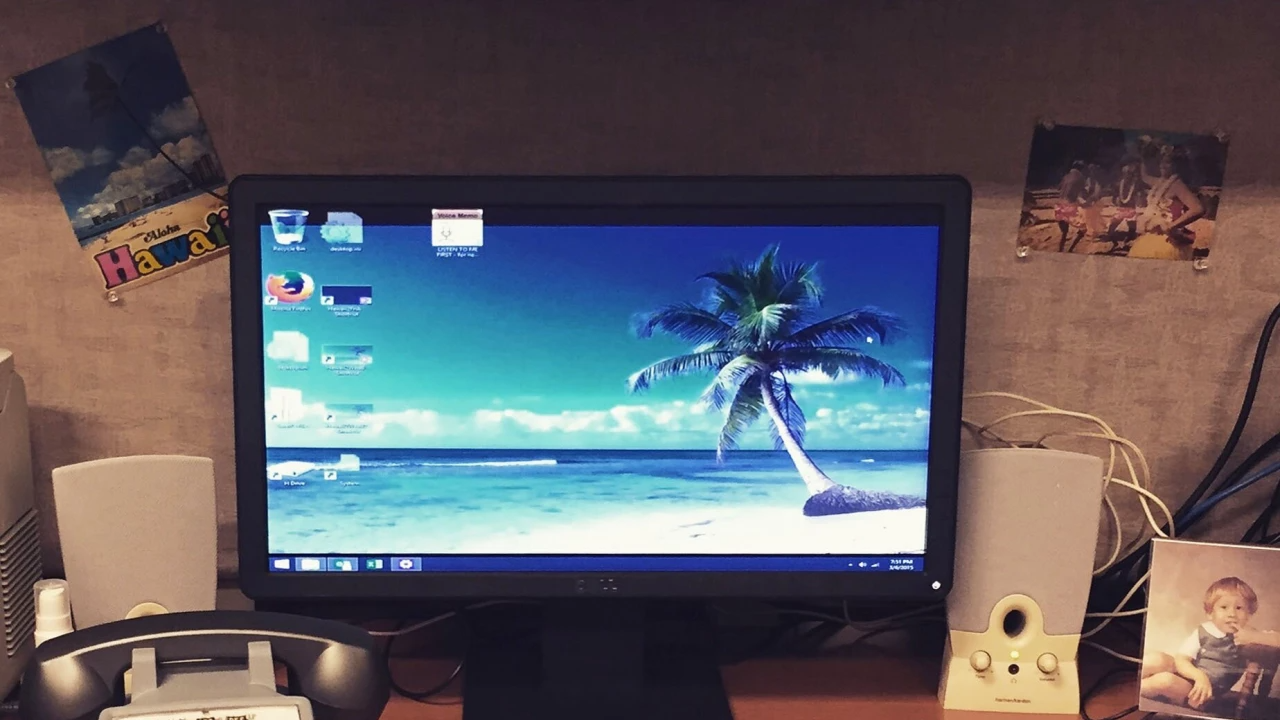

And everywhere, there are photographs and references to Hawaii, where Sarah Jane is taking her first vacation in 17 years of working for Harold, Adams, McNutt, and Joy, LLP. The background to her PC is a photo of a palm tree on a tropical beach. Alongside the cartoons on her corkboard are postcards from Hawaii. In her desk drawer, nestled amongst office supplies and hard candy, are postcards featuring Hawaiian phrases like “Hau’oli Makahiki Hou” (“Happy New Year”) that Sarah Jane has presumably been learning for her trip. They feel, to me, like a cry for help. A daydream of escape from her life as a Midwestern actuary. I’m torn between feeling happy for Sarah Jane that she’s finally getting to go on her dream vacation and sad for her that she will, eventually, have to come back.

But I don’t have long to inspect Sarah Jane’s cubicle before the phone starts ringing and I start getting emails instructing me to carry out tasks. I am here to work, after all. Sarah Jane has helpfully left me instructions on how to do each of her many duties (her carpal tunnel makes writing too difficult, so she prefers to communicate via voice memos). The nature of Sarah Jane’s work becomes quickly apparent. Harold, Adams, McNutt, and Joy, LLP is a life insurance firm and Sarah Jane’s job is to assess risk, estimate lifespan for new enrollees, and keep track of enrollees’ status. Sarah Jane’s boss, Diego, sends me emails with batches of “numbers” (people) who need a “status change.” Meaning they’ve died. His emails are filled with corporate jargon urging words like “synergy” and vague warnings about cutting costs. I am particularly nauseated by his signoff: Diegogogo!

Get Cheyenne Ligon’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

SubscribeSubscribe

When I’m not doing Diego’s bidding, I’m fielding aggressive, bossy voicemails from his assistant James; chain emails from the tech department; and a crabby, competitive fellow actuary who emails me to tell me to stay in my lane and not get too comfortable. And, throughout it all, I try to piece together the mystery of who in the office is sending flirtatious messages to my printer, which start off relatively innocent and then crescendo into aggressive demands to “lick my feet — with (sic) tonge.” Every now and then, I catch snippets of conversation and office gossip from the cubicle next to mine.

Much like gossip in a real office, the story of Temping is cobbled together from tidbits gleaned from various sources. I won’t spoil the ending. Temping is too good for that. But the finale deftly weaves together all the threads the show explores: What is the value of a human life? How do we measure that in a system that values profits above all else? What purpose does loyalty to a company serve to the individual? Where is there room for ourselves and our passions in the structure of a 9–5?

The beauty of Temping is that it doesn’t do the thinking for you. Instead, it allows you to live an experience that you may not have had before and decide what that means for you. No one plans to be a temp; everyone knows that. But Temping gently suggests that no one plans to be a Sarah Jane, either. What is ours to take away is that there is no great difference between us and the temp, and between the temp and Sarah Jane. Without actively resisting, perhaps we’re all just at different points on the same continuum.

Aside from the beauty of its storytelling, Temping is near flawless in its execution. As a performance for one, the participant is the only person in the building. There are no live actors aside from Sandy Johnson, who appears on camera to ensure our compliance with COVID-19 safety protocols. The only communication takes place through email, voicemails, and printer messages. The beauty of Temping is in the precise timing. As soon as I get through with one task, I get assigned another. The minute I put down a piece of paper I’m meant to read, the lights change. As soon as I finish listening to a voicemail, I get an email. I never felt overwhelmed or neglected; everything was exactly catered to my pace.

However, though the timing of Temping was incredibly personalized, I felt like my actions didn’t really have an effect on the outcome of the experience. I don’t expect that anything I did would change the ending or general trajectory, but I wish there were more minor ways I could interact with characters. Aside from my emails responding to direct tasks, I didn’t get any responses from other employees, including an email I sent to Sarah Jane asking about her trip. Perhaps this is because I treated my Temping shift like a real workday. I did what I was supposed to do in a timely manner and didn’t step too far out of line. But I didn’t get the sense that anything I did would get a reaction out of the other characters. For me, this didn’t make me like Temping any less, but I do feel that the description on Dutch Kills Theatre’s website describing each performance of Temping as “unique, depending on which tasks you accomplish and which of your co-workers you decide to trust” is a little misleading. A bit more responsiveness to player agency, and Temping would be a nearly perfect show.

When my shift ended and I left the art gallery, I felt a strange mix of emotions. Relief that I wasn’t the temp or Sarah Jane. Shame that I have been one of them, fear that I might be again. And anger that we live in a system that creates Sarah Janes. I wanted to text everyone I knew to go see Temping, to not put off that trip to Hawaii, to not work late or sacrifice time with loved ones for a job because your boss will never love you back. In the middle of a text to a friend, I got an alert from a travel service letting me know a flight to Rwanda I was tracking had dropped in price. But, I dismissed the notification. Now is not a good time. After all, I have work, and school, and a cat to feed.

Temping continues through December 4. Tickets are $25–45.

NoPro is a labor of love made possible by our generous Patreon backers. Join them today!

In addition to the No Proscenium web site, our podcast, and our newsletters, you can find NoPro on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, in the Facebook community Everything Immersive, and on our Slack forum.

Office facilities provided by Thymele Arts, in Los Angeles, CA.