Setting the Tone, Virtually: Creating the Magic Circle Online (Feature)

How immersive creators can help participants suspend their disbelief at home

“All play moves and has its being within a play-ground marked off beforehand either materially or ideally, deliberately or as a matter of course. Just as there is no formal difference between play and ritual, so the ‘consecrated spot‘ cannot be formally distinguished from the play-ground….

All are temporary worlds within the ordinary world, dedicated to the performance of an act apart.”

— Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens, 1955

The concept of the “magic circle” is one of the most important ones in game design and one of the most applicable to immersive experience design. It describes a space in which the “normal” rules of the world are suspended temporarily, and replaced by new rules of an “alternate” reality; you are no longer where you were, you are now somewhere else. Perhaps in this alternate reality, you don’t speak and you must wear a mask the entire time and everyone communicates via dance. Perhaps in this new alternate reality, you must strive to win a competition to save the universe. Or perhaps in this new alternate reality you find yourself in an unfamiliar occupation as a global ambassador; or in a world where memories can be stored, archived, and analyzed; or in a reality where all sorts of monsters exist, for real.

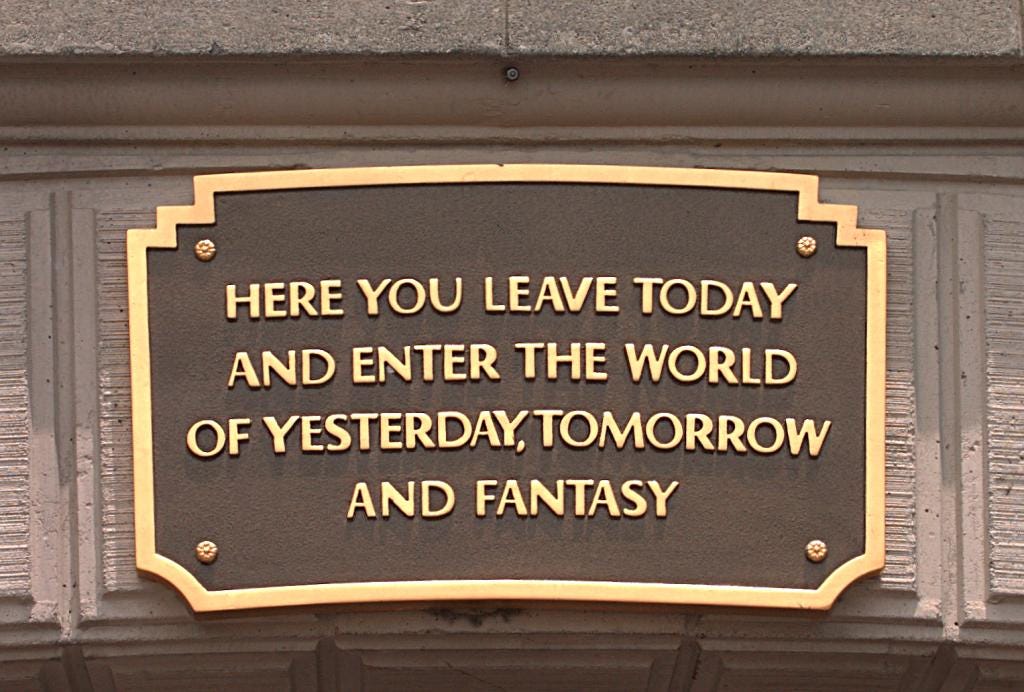

When I think of the “magic circle,” I always come back to one of the most famous examples in themed entertainment: the pathways leading from the entry turnstiles into the rest of the park at Disneyland in Anaheim, California. As patrons go deeper into the park, they literally walk through a tunnel beneath a plaque which reads: “Here you leave today and enter the world of yesterday, tomorrow, and fantasy.” And, once exiting the tunnel, guests find themselves on Main Street U.S.A., loosely modeled after Walt Disney’s hometown of Marceline, Missouri. Or, perhaps, we’d recognize a magic circle closer to the realm of immersive theatre: the dark, labyrinth-like entrance to Sleep No More which dumps disoriented attendees out into the Manderley Bar. Or the waiting room filled with locked drawers and boxes at Then She Fell where participants are whisked away one by one by a uniformed nurse as the show begins.

Where in person immersive events were able to facilitate a “crossing of the threshold” via an in-person physical space, remote events must now work harder to help facilitate our suspension of disbelief. We can no longer count on a mysterious check-in experience, a dimly lit bar, or heavily decorated waiting area to create a certain type of mood before the show begins. After all, it’s difficult to imagine that you’re someone else or somewhere else if you subconsciously know that you’re attending a theatre piece over Zoom at your kitchen table.

So what can online events do to help create this magic circle, virtually?

Crossing the Threshold, Online

Joe Ball of Exit Productions (Jury Duty) advises that creators not simply try to digitize the same onboarding and offboarding processes they had before when their shows were meeting in person. “It will be a bad imitation and the limitations will be obvious,” he warns. Instead, he advises that makers view this issue not as a problem, but as an opportunity, and try to get excited by that.

Kendra Slack of Linked Dance Theatre (Like Real People Do) observes that, “… [for] live shows, the audience usually gets to travel to a physical space so that element of journey and arrival is already inherently present…. it’s important to consider how we can create this same feeling in the virtual world.”

Ana Margineau of PopUP Theatrics (Long Distance Affair) compares it to packaging, saying, even if the “content is the same, but the design of the box is really everything in creating the mindset.”

Evan Neiden of Candle House Collective (Under the Bed, claws) agrees. “Theatre at a distance is uncharted territory to most audiences, meaning they don’t really know what to expect…. Rather than resisting distance and remoteness, we ought to celebrate it. That’s where the magic is.” He views the audience experience holistically, emphasizing the importance of managing their expectations. To him, this means “considering your audience’s entire experience with your work, from the very first time they hear about it to the moment the ‘curtain rises.’”

When designing their immersive experiences, he asks, “What does a prospective audience member see first… and why? What does it tell them about your experience’s tonality, interactivity, and purpose? Does this threshold make them feel welcome and, if so, should it?”

“Most importantly, when show-time comes around, what kind of ‘ready’ would you like your audience to be?” he ponders.

Live Streamed Theatre’s Relationship with Cinema

Multiple immersive creators have noted that creating remote theatre at this time feels more akin to film than before. ARG pioneer Sean Stewart, who is currently directing Roundabout, an interactive play for Australia’s National Institute of Dramatic Arts specifically tailored for performance on Twitch, notes that this current era may be a comeback for live theatre over TV and film, since theatre “can deliver a live, interactive experience that cinema can’t come close to matching.”

“Since pretty much any virtual immersive theatre show now relies heavily on camera-work of some sort, especially Eschaton, we wanted to draw from other media,” states Tessa Whitehead of Chorus Productions, as they looked at TV, film, and video games for inspiration. She says the team asked themselves, “[In] worlds like Myst and The Witcher, how do they transport their audiences into heightened, faraway lands each and every time they log in?”

Ana Margineau of PopUP Theatrics says that making their Long Distance Affair shows “as theatrical as possible” with “moving actors and moving cameras” was important in keeping their experiences feeling dynamic; otherwise, they felt as if their show was simply competing with Netflix for people’s attention. The team specifically wanted to avoid the same static feeling as every other Zoom call by playing up these aspects. Margineau also advises that even if your performers may be dialing in from a realistic, everyday environment, “it doesn’t necessarily mean that you have to use it realistically.”

Long Distance Affair cleverly punctuates every scene with the performer turning their camera off and playing a short snippet of music which acts as a sort of “credits” scene before attendees are returned to their Zoom lobby. Margineau also says the team didn’t realize just how crucial a custom soundtrack was going to be until they were in rehearsals and spending a lot of quiet, idle time on Zoom; once one of the stage managers figured out how to add songs like “London Calling” and “Empire State of Mind” to the background, the experience felt more lively and engaging.

Haley E.R. Cooper of Strange Bird Immersive echoes this approach in using a multitude of filmmaking techniques so that their experience, Zoom Tarot Readings with Madame Daphne, still feels special and magical in a time when people can’t physically gather.

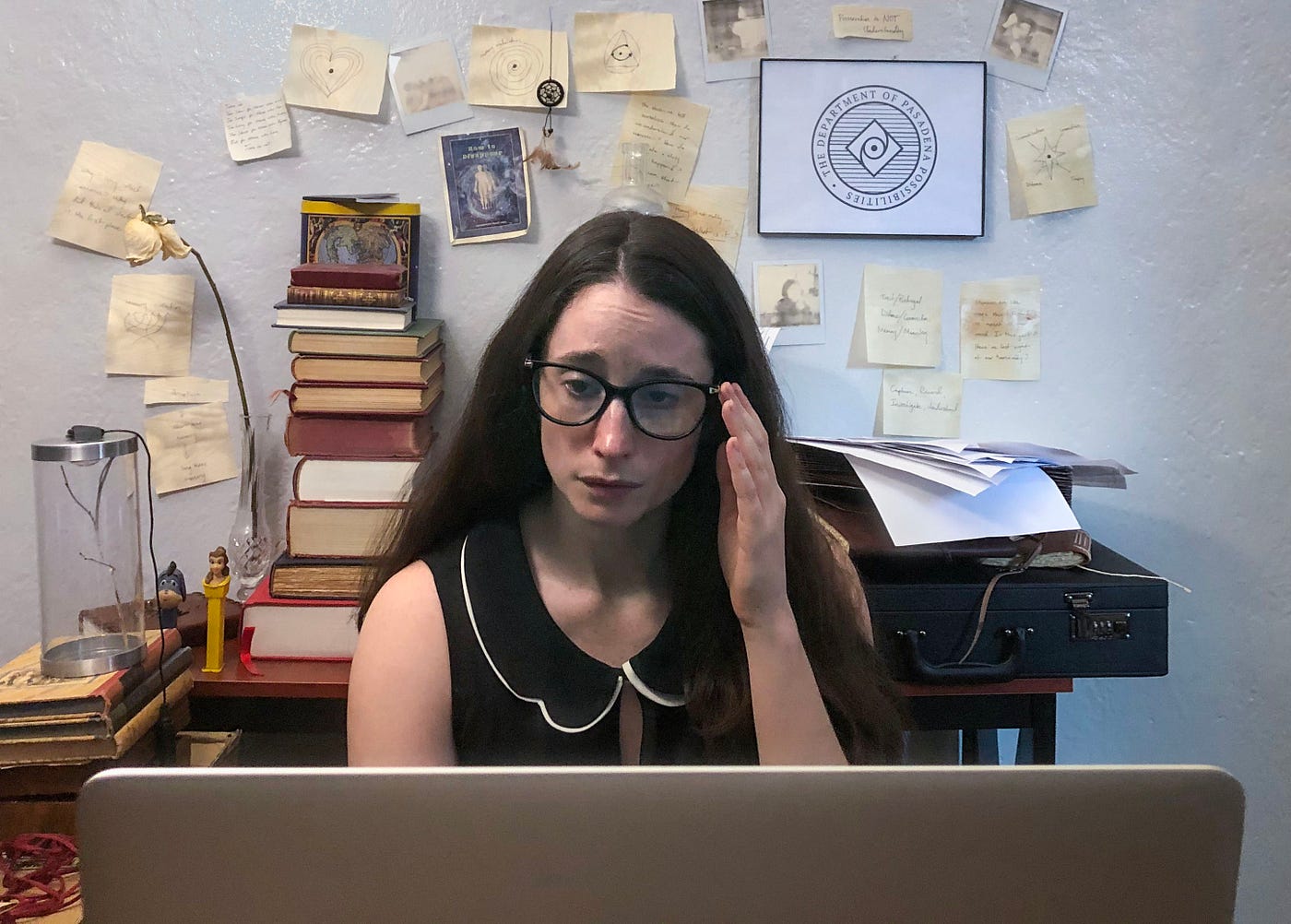

Says Cooper, “We spent hours testing cameras, setting up the shot, and fine-tuning the lighting, so that what you see when you first arrive is something far from your usual Zoom encounter. Once you join the meeting, you see show-level production values: our character is in costume and makeup, and her space looks exquisite, setting the tone for the encounter.”

“We’re all videographers now,” she adds.

Messages, Recipes, and Rituals

Some immersive creators have been experimenting with in-world communications in the pre-show experience. I’ve received a number of these, ranging from a reminder from the “human resources department” about “my upcoming job interview” before an interactive show, a map for my “afternoon hike” before a remote escape room, and even a PDF “court summary” for my “upcoming jury duty service” before a team-based live action game. This kind of framing, in addition to the in-world message, helps participants get into the right headspace before the show even starts.

Kendra Slack of Linked Dance Theatre says, “[Pushing] the magic circle out to include the time before the experience even starts especially helps these online worlds feel more immersive because they don’t have the luxury of surrounding someone in a physical environment, rather they have to do that through creative mood setting.” Haley E.R. Cooper of Strange Bird Immersive notes that “You need to send an email to do a Zoom show anyway. Why not make them in-world?”

Get Kathryn Yu’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

SubscribeSubscribe

And while some higher-end, more expensive experiences like The Present have mailed boxes of props or ephemera to participants ahead of time, most productions have more constrained budgets, and can try to achieve similar effects digitally or by using household items. These pre-show rituals can help eager participants make their everyday environments feel a bit more special before the experience begins and get attendees into the desired mindset through taking specifically designed actions tailored to your experience.

The Delegation asks that attendees bring a box of matches or a candle to the virtual show (due to the Hotel’s ongoing power outages) and a book (to act as a replacement for the Gideon Bible). Like Real People Do instructs participants to dress as they might for a job interview. And Ladies of Versailles offers a host of suggestions for getting into the mood via PDF, from appropriate dress (anything satin or ruffled will do) and decor (perhaps a red blanket thrown over a chair to recreate a “throne”) to a list of recommended beverages (a variety of champagne-based cocktails or bubbly water with fruit juice).

Other experiences like the popular virtual nightclub Eschaton set the tone through a series of pre-show instructions on a custom web site: lowering the lights, dressing in cocktail attire, and pouring oneself a drink (presumably alcoholic) before the club’s doors open. Creator Dustin Freeman of Escape Character has even gone to the lengths of building a small “at home” set in order to get into the right mindset to attend Eschaton.

“I think if, as an audience member, if you’d dress up nice for an in-person show, then you might as well build a nice set for a remote show… [for] the show’s benefit, but also your benefit, psychologically,” he says.

So while not every ticket holder will go to these lengths, a little bit of at-home set up can go a long way to helping attendees feel like they’re at a theatrical event rather than dialing into class or a work meeting.

However, Melinda Lauw of Whisperlodge emphasizes that not every audience member will follow the pre-experience instructions to a tee, saying, “There’s no real way we can control how the audience prepares, so our approach was to over communicate, as well as accept and be OK with the fact that some people still won’t follow the instructions.” She recommends breaking up information strategically throughout the course of the participant’s journey so that they don’t become overwhelmed with too many things to do.

Making Zoom the Innermost Layer

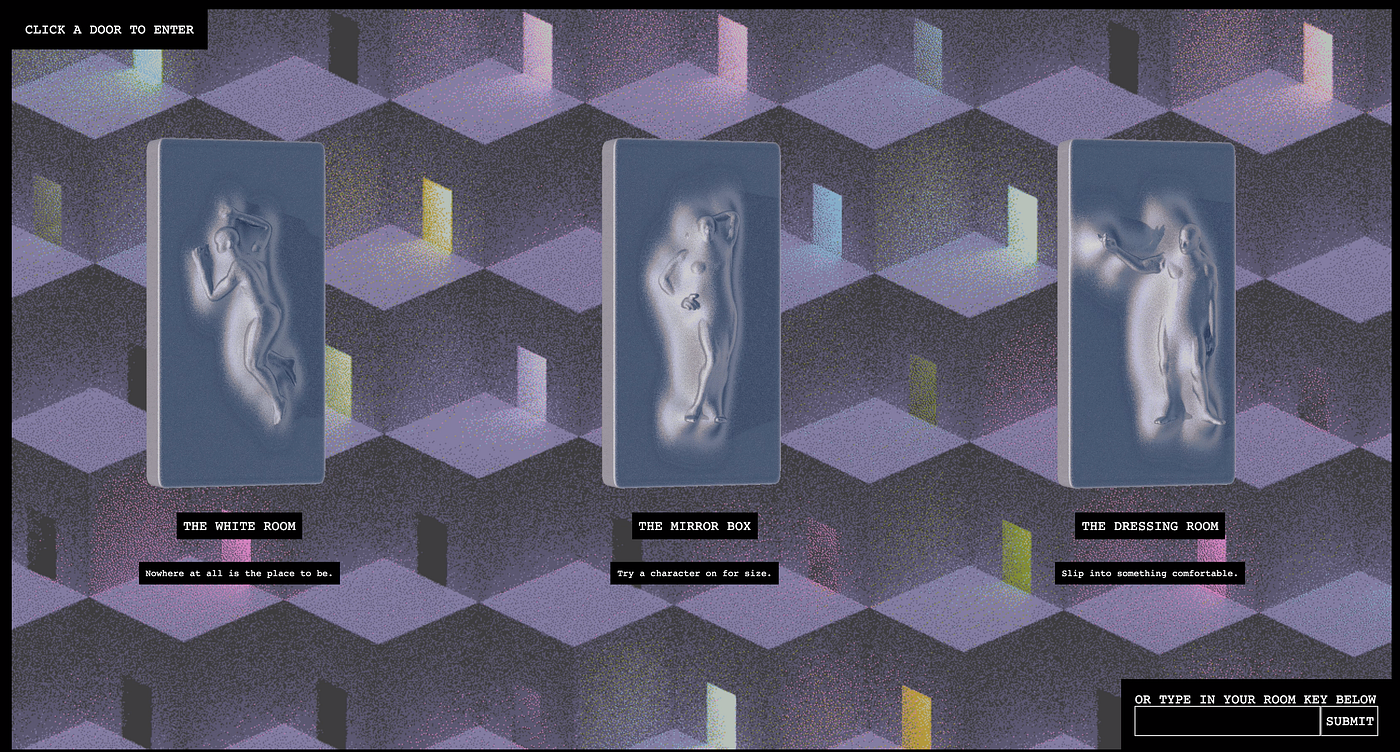

While waiting for the doors of Eschaton to open, participants sit in a virtual waiting room on the web. Once the experience is about to begin, they’re treated to a mysterious welcome video, talking about the history of the shuttered nightclub and how best to make use of their allotted 60 minutes inside; immediately afterwards, participants are let loose within a maze-like web site which serves as a jumping off point to various Zoom rooms, each one containing a different performance.

These kinds of “crossing the threshold” transitions can help participants know that they’ve entered a liminal space as well as providing space to focus and prepare themselves for what comes next. Tessa Whitehead of Chorus Productions notes that it was important for the Eschaton team “to learn lessons about creating liminal spaces for audiences who are sitting at home.” She says, “…we tried to pay attention to as much detail as possible, thinking through every little thing. These were the considerations that led us to creating a custom-designed website and ‘entrance’ into Eschaton, instead of just jumping into Zoom directly.”

On the other side of the mood spectrum, PopUP Theatrics’ Long Distance Affair uses a virtual lobby with a completely different vibe. The space is managed by two hosts — Henrik Cheng and Michelle M. Lavergne — who spin a playlist of travel-related songs while using virtual backgrounds that mimic an airline’s “departures” board. The show’s two “navigators” (part facilitator, part performer, part stage manager) encourage conversation between strangers while also moving participants between breakout rooms and troubleshooting microphone and camera issues, all while using airport-specific language. The result is a freewheeling, party-like atmosphere that harkens back to travel’s golden age.

And Coney’s The Delegation takes a slightly different approach by using a custom web site to facilitate a faux “hotel check in” process as players enter a virtual version of the Hotel Zajec; participants are issued a virtual room key before the two teams of delegates meet up in the “hotel’s virtual lobby” on Zoom. The creators also ask that participants rename their usernames on the tool with their associated delegation and room number, as a digital name tag. All instructions and materials are presented in both English and Russian in the livestream, as if participants were truly part of an international summit, adding another aspect to the realistic feeling of the experience.

This digital welcome doesn’t have to be as elaborate as a custom web site or video, though. For example, Coney’s Telephone uses a simple handkerchief in front of the webcam to act as a “virtual curtain” to indicate when the show has begun. And to prepare for a session of Whisperlodge Virtual, a digital version of the ASMR spa, participants enter a waiting room and are treated to several minutes of pre-show music; they’re also asked to turn the brightness of their screens down, to facilitate relaxation, demonstrating that a simple audio track can also help set the mood.

Melinda Lauw of Whisperlodge also advises the creators to either lean into the fact that they’re using Zoom or explicitly try to subvert the platform. “Audiences are so aware of their screens and their interfaces. You can either choose to acknowledge them and use that fact to your advantage, or go the other way, create enough story, or intrigue, or activity so that they forget and transcend them,” she says. However, while it might be tempting to use every available feature of your chosen platform, sometimes simplicity is the better approach. She also cautions, “Don’t feel pressured to use all the technical tools available, just what you need.”

Sticking the Landing

The ending of a virtual experience also needs to be carefully considered and designed, otherwise — like the end of an awkward conference call — it can feel sudden and abrupt to the audience. Jessica Creane of Chaos Theory does a small but meaningful ritual towards the end of her remote experience: the audience is directed to cover their webcams with their thumbs to show the flow of blood beneath the skin. The crowd falls silent and focuses upon being together. And the experience’s final, hilarious moments consist of a recorded video that serves as the punchline for an earlier joke.

Nicky Romaniello of Linked Dance Theatre finds that sending your audience back out into the real world with “a rug pull, or sense of ‘Wait, was that it?’ can… cheapen even a well-built show,” emphasizing the importance of designing the experience’s final moments. He observes that “where there is no opportunity to leave the audience in an environment to reflect on the show, you have to find an in-world exit that feels earned and hopefully leaves the audience feeling satisfied and reflective.”

Says Haley E.R. Cooper of Strange Bird Immersive, “Our experience starts with an email that looks and feels like a part of it, and then it ends with a small surprise in the thank you afterwards.” This specifically designed welcome and goodbye “bookend the ritual of attending, making guests feel like they participated in something special,” she notes.

For some creators, a lingering, more ambiguous off-boarding can prove to be more satisfactory. After the final episode of Like Real People Do: Long Distance Relationships Division, the audience receives a post-ending, post-script message from one of the characters, implying that the continuation of her story and the continued existence of the show’s storyworld.

Tessa Whitehead of Chorus Productions states they had a similar goal in Eschaton, saying “We want audiences to have the feeling that there is more to see and do in Eschaton than they can get to in an hour, and when they leave, even if they don’t come back, it’s is a universe that keeps existing and living parallel to ours.”

Carrying Pandemic Lessons Forward

Despite the ups and downs of being a theatre maker during the time of a pandemic, many immersive creators are optimistic about the future, even if they recognize they’ll be performing remotely for the time being.

“I’m so proud of the immersive community that out of all the horror and constraints (it’s an industry about being there, embodiment, and touch, for crying out loud!), we’re finding new ways to engage and pursue intimacy. I love it,” says Haley E.R. Cooper of Strange Bird Immersive.

Joe Ball of Exit Productions is also hopeful that the knowledge gained from making theatre during the pandemic will endure. He says, “It’s an amazing moment where we have to really think about that specific part of our craft as we can’t rely on our usual toolbox of space, lighting, and design. I hope that I keep that as we leave lockdown.”

“It’s a good time to play with utopian dreaming,” he adds.

Discover remote, online, and socially distant experiences on our Now Playing: Immersive for Indoor Kids page.

NoPro is a labor of love made possible by our generous Patreon backers. Join them today!

In addition to the No Proscenium web site, our podcast, and our newsletters, you can find NoPro on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, in the Facebook community Everything Immersive, and on our Slack forum.

Office facilities provided by Thymele Arts, in Los Angeles, CA.