Resurrect the Voices of Our Traumatic Past in ‘The Black History Museum…According to the United…

Zoey Martinson and company deploy a staggering array of styles to bring history to life

My dad’s black. My mom’s white. I haven’t seen my dad since I was a little kid, so my cultural upbringing happened with my mom’s family. They’re white liberal Northern Californians of Scottish heritage. I talk like them, dance like them, vote like them, read like them. The whole deal. And even though my dad’s black, I look white. Nobody ever thinks I’m mixed. Well, there was a very intense man who yelled at me once in downtown Berkeley: “I know your father’s black! I know! You can’t hide it from me!” I don’t try to hide it, but most people don’t see it, which means whoever my ancestors were, I wear that invisible shield of privilege. I walk the path of white privilege. But I’m not white.

Except I’m not black either. I don’t have a black card. I should not have a black card. So I was pretty intrigued when black cards — physical little black cards with “HONORARY BLACK CARD” spelled out in embossed letters — are handed out to every audience member at the beginning of The Black History Museum…According to the United States of America currently playing at HERE Arts Center in New York City.

In The Black History Museum…, conceived and directed by Zoey Martinson, the first character we meet is The Guide. When he starts talking, it’s easy to recognize what sort of stereotype he is, because he tells us. “I’m a magical mulatto. Now, I’m sure you all know the trope of Magical Negroes in films, helping and guiding the protagonist toward success, in a selfless and mystical way. Well, a Magical Mulatto is basically the same thing, but for Off-Broadway theatre.”

The Magical Mulatto in question is The Guide, played by co-writer Robert King, is the first of many examples of Martinson’s canny utilization of racial tropes. She uses them to simultaneously charm and disarm the audience, entertaining us even as she cuts to the core of the kinds of destructive tropes that could only exist in a country shaped by a profound history of institutional, endemic racism.

The Guide continues: “I know some of you are nervous because you are…very white. And ‘white guilt’ is a very real thing. Half of me is afraid this show is racist… But the other half of me is magical, so, I’m doing alright. Anyway, have no fear, white friends! I have personally consulted with the black community’s secret council, and have obtained permission to grant all pigment-deficient members of this audience an Honorary Black Card.”

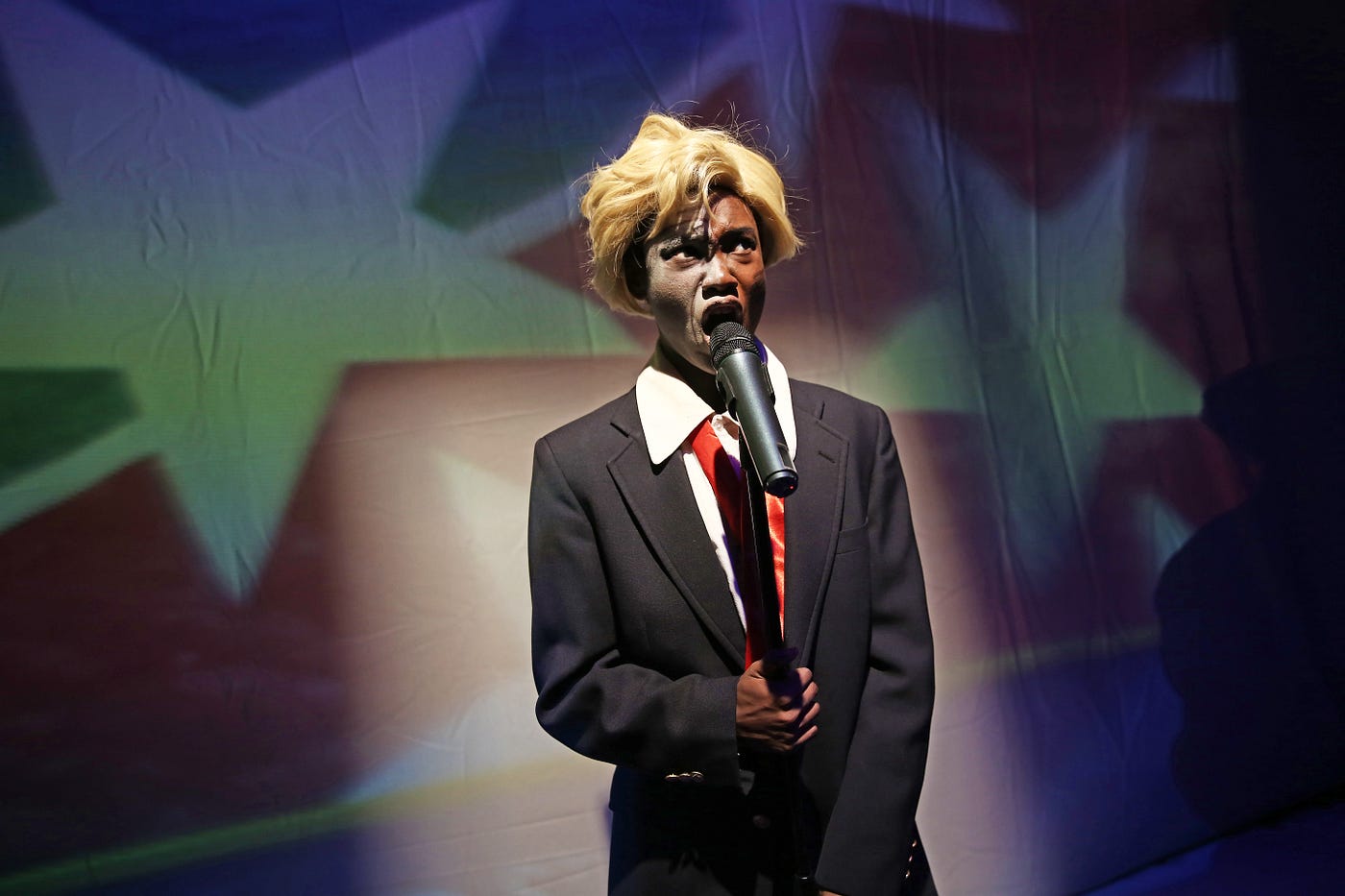

From there we go deeper into the space and meet The Descendant (played by Kareem M. Lucas, another co-writer of the show). If The Guide came to us with the grin and helpful demeanor of the Magical Negro (or Mulatto) Trope, The Descendant is something else altogether. Speaking with rhythms so sharp you can hear the line breaks, The Descendant is anger and knowledge, a prophet whose vision looks to the past. Lucas brings a heady, passionate, propulsive rhythm to his performance as The Descendant. The language of The Descendant is the backbone to the whole show, and Lucas rises to the task with exceptional presence and technique. His voice is powerful and precise, rolling on waves of anger and passion and pain, pulling and pushing the audience relentlessly. As The Descendant tells us, “I am The Lookout / I am The One Who Sees That which we call / The Past / Open your eyes / Your minds / Your hearts / Receive all this history / Which I hope / To pass on to you / For that is my duty / And / This is where I live / I am / The Descendant.”

The Black History Museum… is a piece that brings a great deal of approaches to bear on a singular goal: bring the audience to the same place where The Descendant lives. It wants us to not just acknowledge the trauma at the heart of American history, but bring our bodies there, feel the history in how we move and feel and think, transform us, and put us back out into the world as Descendants ourselves. What else would it mean to hold on to an Honorary Black Card?

Get Zay Amsbury’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

SubscribeSubscribe

Martinson, along with co-writers King, Lucas, and Jonathan Braylock deploy a spectacular array of techniques, tools, and tones to achieve the goal of turning the audience into a group of descendants. A different points the piece employs sequences of contemporary dance, a participatory game show, historical documents, individually curated art galleries, solo performances, scripted theatre, face-paint, call and response, farce, heart-wrenching audience interaction, a full on 70’s dance party, a church meeting, and flat out slapstick humor. It is a dizzying display of styles, and if one doesn’t get to you, another one probably will.

During one segment that evokes the terror of the Middle Passage, the audience is put into a cage. Outside of the cage, dancers depicting slaves writhe in pain. The reversal is stark. We stand, a mostly white audience, looking out from the inside of a cage, at slaves expressing in stark movements the pain of the middle passage. Suddenly, one dancer reaches into the cage, grasping the hands of the man next to me, weeping and begging him for some sort of relief or freedom or connection or some other thing that the man can in no way provide. He can only offer up a look of concern, and then a choking, uncomfortable laugh as she is dragged away from him, subjected again to the grinning depravations of the Founding Father.

All of this is harrowing stuff, as it should be, but The Black History Museum… employs skillful shifts in tone to keep the audience from getting exhausted. As soon as something seems like it might be too much too soon, the show switches gears. The difficult Middle Passage section might open up into a slower, solo section of wandering around contemporary black art galleries, or uplifting historical documents, or biographies of heroes from black history. While the piece is emotionally and intellectually challenging, it never becomes overwhelming, a singular feat given the show’s content.

The section that held the deepest surprise for me in terms of emotional impact was a more scripted piece. The scene begins as a satire on the “diversity training” that has now become omnipresent in offices around the country. In this case, the meeting, led by a comically oblivious HR representative played with abandon by Marcia Berry, reveals how diversity training framed by the blinders of privilege can end up emboldening those who already have a platform, and disempowering those who would be punished if they were to say what they really feel. As the White Employees (in pitch-perfect performances from Tabatha Gayle and Langston Darby) inflict microaggression after microaggression on the lone Black Employee, her anger builds and builds until she breaks out of the naturalistic frame of the scene and starts to dance. Latra Wilson’s performance as the Black Employee is a masterful articulation of restraint and release, as she hashes out with angles and elbows and precise, halting rhythms all the thoughts and feelings that the company provoked with their “diversity training” and would punish her for if she said out loud.

There’s a lot going on in America right now. It can be exhausting just to keep up with the news. You might think it’s just too much to go see an immersive play about Black History. If you do think that, it may be proof this is the exact show you should go see. The Black History Museum…According to the United States of America is as funny as it is sad, and as achingly earnest as it is shrewdly ironic. It does whatever it needs to do to get you to pay attention to the voice of The Descendant, which is the least you can do as long as you’re holding your honorary Black Card.

There are many traumas that live in the heart of our country. Some of us are privileged to be able to forget that fact. To the extent that the production brings those of us who have had the privilege to grow distant from the trauma of slavery and the endemic, enduring racism of our country, The Black History Museum…According to the United States of America is essential viewing.

The Black History Museum…According to the United States of America has concluded its run at HERE in NYC.

NoPro is a labor of love made possible by our generous Patreon backers. Join them today!

In addition to the No Proscenium web site, our podcast, and our newsletters, you can find NoPro on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, in the Facebook community Everything Immersive, and on our Slack forum.

Office facilities provided by Thymele Arts, in Los Angeles, CA.