On Being, Virtually, at Cannes XR (Feature)

What happens when you put your virtual reality festival into virtual reality?

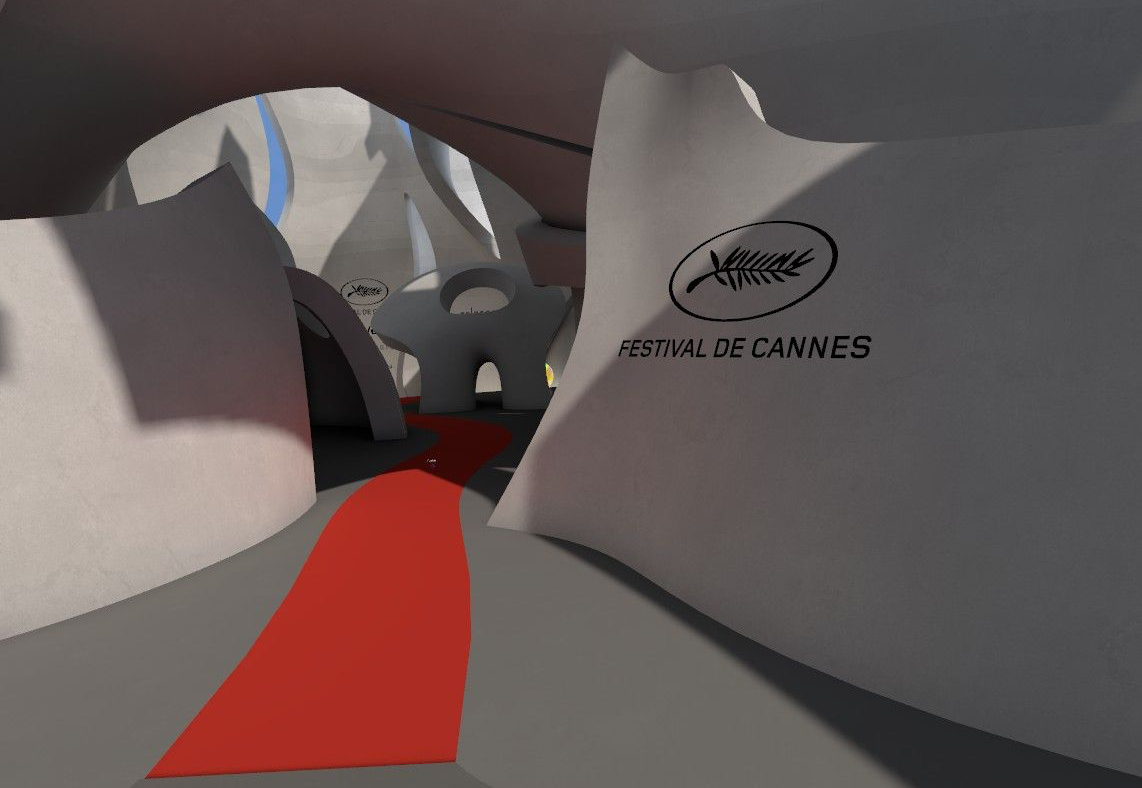

In late June, the Marché du Film, Tribeca, Kaleidoscope, The Museum of Other Realities (MOR) and Veer VR partnered to present Cannes XR Virtual, a program “dedicated to immersive technologies and works,” as a pivot from holding a traditional in-person industry festival due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The virtual festival occurred within the Museum of Other Realities on Steam and was available as downloadable content add-ons from the Steam store. Anybody with a PC VR headset like an Oculus Rift and HTC Vive was able to experience 55 different VR pieces, from 360 films to interactive 6 DOF stories, with a few simple but large downloads. Plus, the hosting platform Museum of Other Realities, which is normally $19.99 on Steam, was also made free during this time; all in all, this added up to an enormous amount of VR content being released for free to the public.

Sure, it’s a little cumbersome to have to hook up my Oculus Quest to my PC, install Steam, install Steam VR, and download over 60 gigs of content, but I can actually experience the entire virtual festival from the comfort of my own home over the course of a week and a half. In normal, pre-pandemic times, a visitor might be lucky enough to see 3–5 XR pieces in one session at a festival of this scale. I, personally, have many memories of getting in line an hour before my allotted time at the Tribeca Virtual Arcade or coming back multiple days to try to get into a “sold out” exhibit. This time around, I don’t have to deal with booking time slots or trying to be first to a kiosk to get into a virtual queue, hoping to snag one of a few limited spots. Many of the works on offer on the festival circuit may never make it into people’s living rooms in the future. It’s a fact I’m acutely aware of as I try to take in as much VR content as I can during this limited time event.

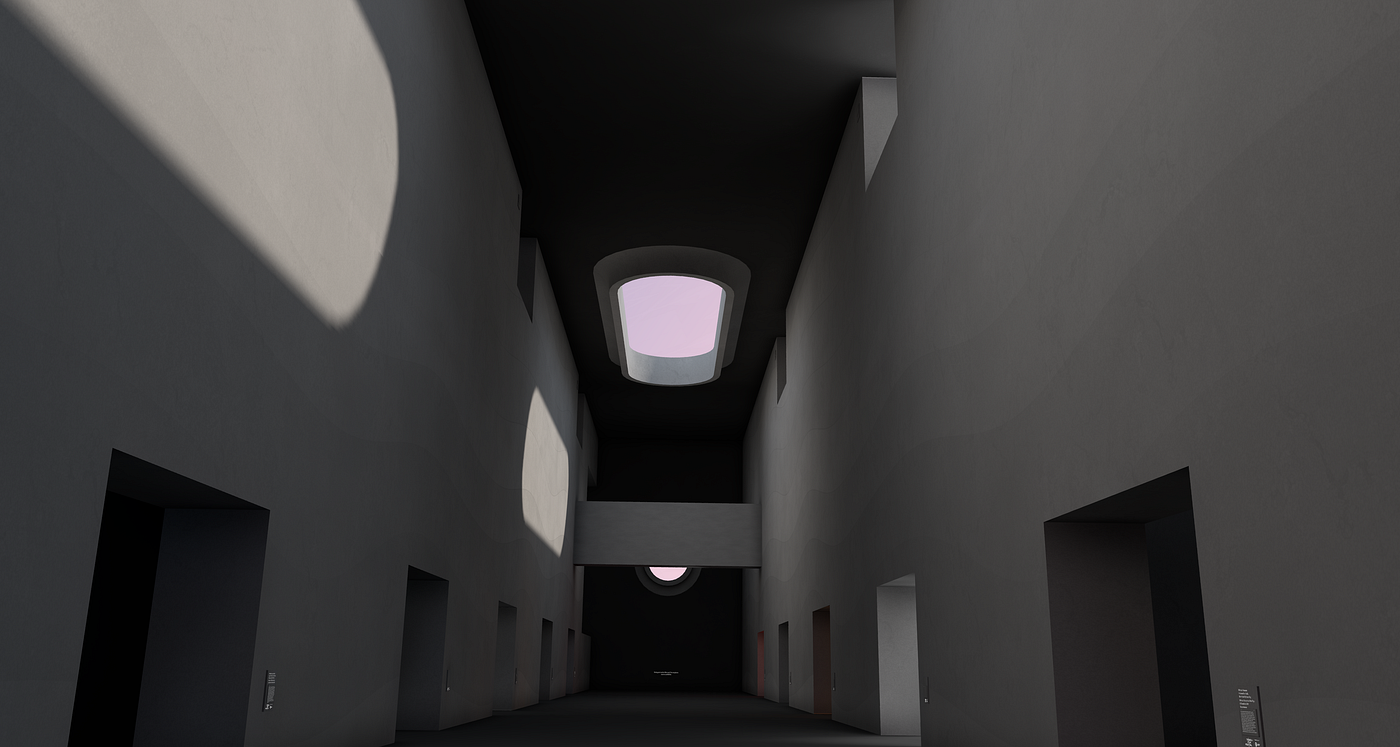

With my headset on standby, and the fan on my PC kicking into high gear, I peek at the map the press agent has sent me about the Cannes XR exhibition in the Museum of Other Realities. There’s a simple diagram implying a hub and spoke model with one spoke for each sponsored showcase from Tribeca, Positron, Kaleidoscope, and Veer. It seems straight forward enough. So why am I lost? Putting the headset back on, it’s clear that I’ve somehow wandered off the main path and am in the Museum itself looking at the permanent collection. The map I have doesn’t show the relationship between the rest of the MOR and the Cannes exhibit I’m looking for. I decide to retrace my steps, backtracking as fast as I can down the hallway (plop, plop, plop goes the clever liquid-y animation they use to show you teleporting). I’m headed back to the entrance (plop, plop, plop), confused, and determined to find help.

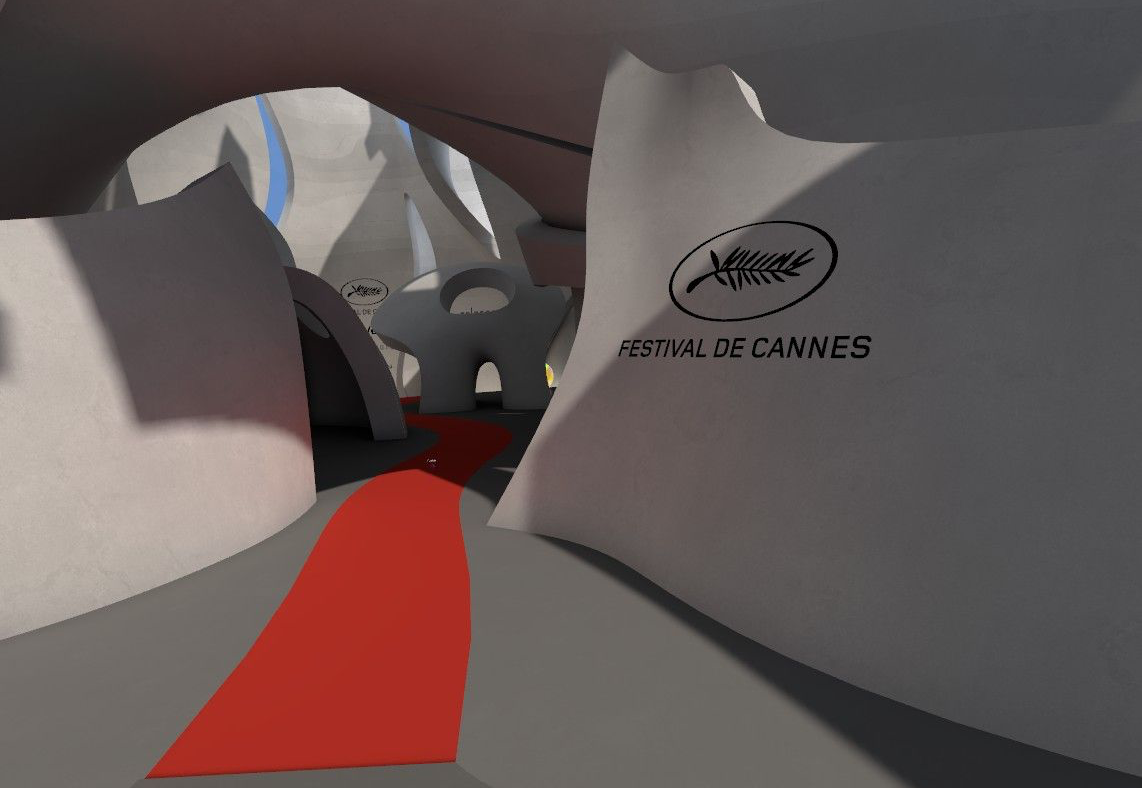

I come upon a very cool-looking floating table-sized virtual map filled with a multitude of dots (each one representing a current visitor) and a docent; his avatar is a series of colorful 3D shapes, a swirl of an abstract head, torso, and two hands with a whole lot of emptiness in between. I realize the location of the 3D map is unfortunately placed in a way that it’s easy to miss if you’re coming down the virtual stairs from the entrance. I’ve also somehow completely bypassed a mirror where you can preview your avatar and change your appearance. Whoops. Perhaps later, I tell myself. I’ll make do with these red blocks for hands, for now.

I soon plop myself next to the docent, squinting to read the username billboarded above his head as the text flips backwards and forwards automatically. Is it the low resolution of my headset that makes it hard to read? Is it rude to linger nearby until the text flips back? Or is it the usage of white text upon a white wall in a brightly lit space which is confounding me? He has his hands placed above his head and turns, presumably, to address me. A dialog box suddenly appears showing me how to “speak” in this strange place I find myself; presumably to prevent trolling and abuse, voice chat in the MOR is controlled through this permissioning system. Is my mic on already? I see an image flash in front of me, it’s showing me which button to press to initiate talking, but the diagram exactly doesn’t match what I’m using (an Oculus Touch controller); I press what I believe to be the correct button down and end up holding it for the duration of our short conversation. If I let go of this button, is the connection interrupted? Is this like a telephone or a walkie talkie or a Zoom call where I’m on mute? Am I even doing this right?

The helpful docent shows me how to use the map to teleport directly into the auditorium where a series of Cannes panels has already started (whoa!), as well as how to speak to other users in the experience, and “float” to make myself taller (sidebar: I immediately feel sick when trying to float). I ask him why the YouTube stream of the panels isn’t working and he confirms that they’re having technical difficulties but I should be able to watch them in VR. I thank him for his assistance and teleport myself directly into the Cannes section. Plop, plop, plop.

I find myself surprised that even though I’m in VR, the space for the conference segment of Cannes XR is essentially a projected Zoom window. I can see and hear the speakers on a flat rectangle in the space but nothing about the experience feels “spatial” at all to me. No wonder I’m the only avatar in here, watching. Without access to the Zoom call itself, I can’t ask questions or offer comments during the panel or participate in the backchannel that surely is happening, somewhere. I decide to put down my Touch controllers and turn up my Oculus Quest’s volume. My Quest is still connected to my PC so it’s now essentially acting as a very expensive speaker as it rests on my kitchen table. Later on, I realize that another person has attempted to speak with me; when I put my headset back on, I see a dialog box has popped up, asking me to accept or decline their request. Both options feel awkward: engage with a stranger in VR while we’re both theoretically listening to a panel or decline, knowing that I’ve shut down a potential friendship or collaboration. I’ll never know. I’m sorry, stranger, whoever you are.

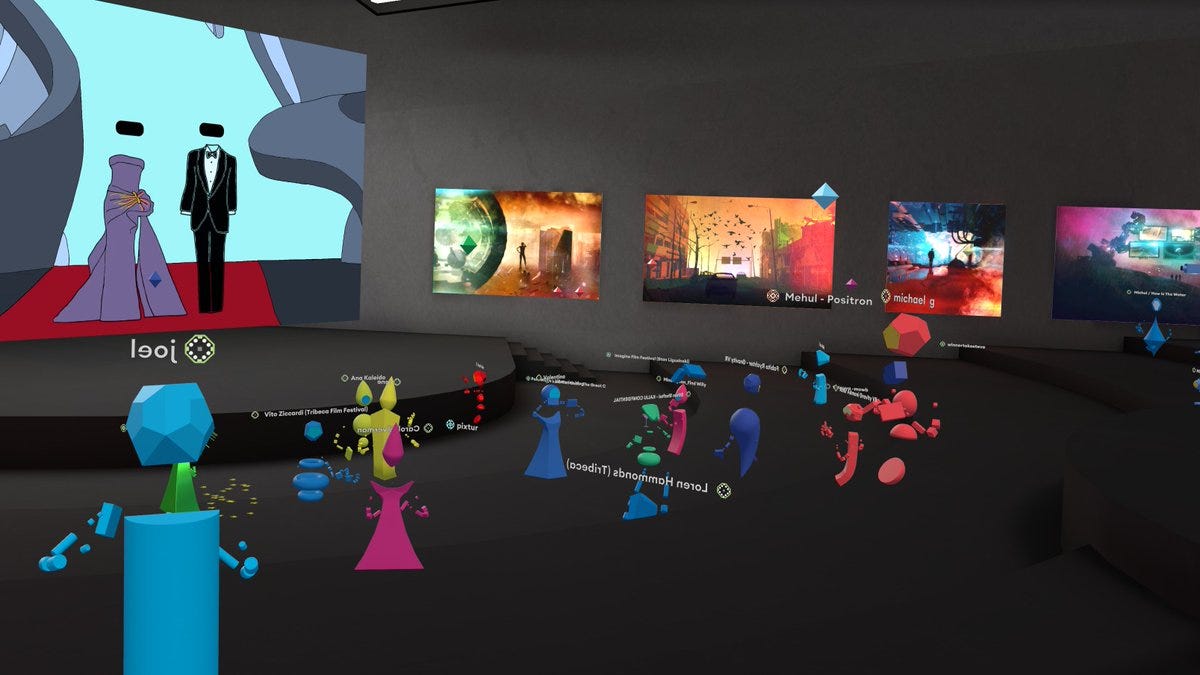

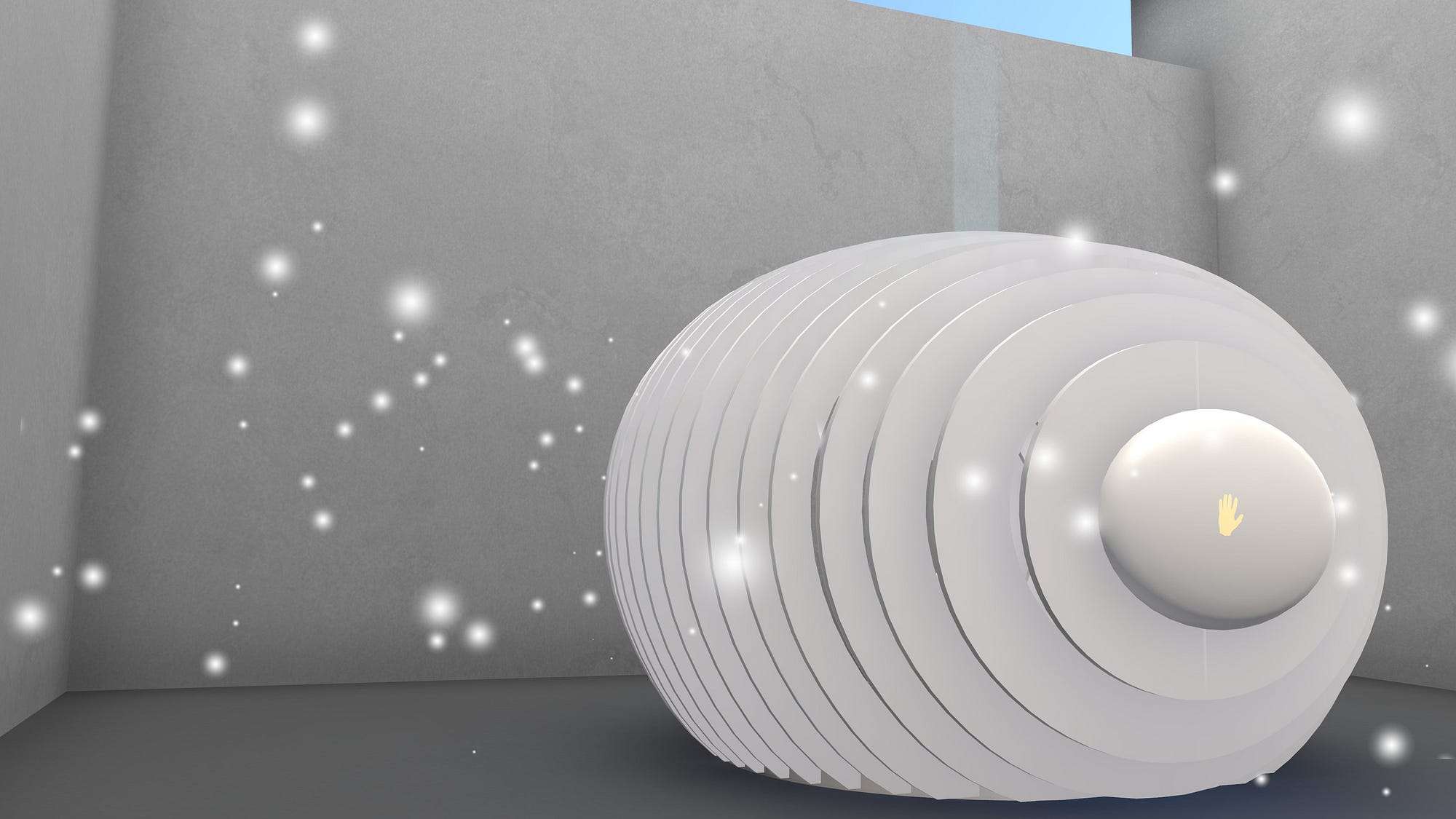

Later on, I exit the auditorium in search of the VR exhibitions. I see two long enormous hallways forming a “V” shape, one labeled “Tribeca” and another labeled “Kaleidoscope.” I’m standing at the V’s vertex but I’m not sure where to find the Veer and Positron pieces. I can hear my theme park professor in my head, saying that this built environment lacks a “weenie,” that is, a tall object in the distance for your eye to rest on and an implicit goal to head towards. I eventually head towards the Tribeca Virtual Arcade showcase, winding myself down the hall, stopping to read the names of each piece as best I can. It’s awkward, given the limited field of view of my Quest and the maximum teleportation distance allowed inside the MOR; I wish I’d had a better headset. The pieces are set up like a looped film might be in a real-life museum. Each one has a large flat wall facing the main hallway and two doorless entryways. What’s inside each room isn’t apparent until I turn the corner to enter; there’s usually no hint of theme or subject matter from the outside. Once in, I see some artists have customized their space. I especially appreciate the Victorian era room set up for Mary and the Monster, the enormous egg sculpture you must enter to start Fly, as well as a gorgeous circular sculpture of handwriting floating in the air for Queerskins. To truly give yourself to an immersive experience is to cross the threshold and become one with the magic circle; I can see some efforts to reproduce this effect in these particular installations, to prime the viewer for what they’re about to experience, and I appreciate the extra effort.

The works at Cannes XR are all interesting even if some of them are simply teasers, demos, or working prototypes. A number of them use scale and perspective in new and interesting ways. In A Linha, a number of gorgeously tiny figurines on tracks are unable to progress forward without a series of levels and wheels that only I could control. In Minimum Mass, I feel like a god twisting and turning the dioramas to view scenes unfolding from different angles. And in Gravity, I can fly among a stew of falling objects in a surrealist world. Virtual Becomes Reality allows me to visit Stanford’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab and participate in some of their groundbreaking research experiments from a first person perspective.

But the most powerful pieces here take a page from immersive theatre and allow me to become part of the story; by casting me, the viewer, as part of the world and making that world human-scale, I feel more engaged, overall. And none of these use interactivity purely for interactivity’s sake, which can be a common pitfall. In The Book of Distance, I am a visitor and friend to artist Randall Okita as he walks me through the VR memory palace he’s built, reviewing the life history of his grandfather who emigrated from Japan to Canada and then ended up in an internment camp; The Book of Distance is lovingly rendered and going through the experience is extremely touching. In Fly, by Charlotte Windle Mikkelborg and Amaury La Burthe, I am a time traveler bearing witness to important historical moments in flight and then eventually empowered to “fly” myself, a testament to VR being used best for situations which are improbable or impossible. And in the powerful Violence by Shola Amoo and Nell Whitley, I find myself torn in considering my own agency, feeling somewhere between a Good Samaritan and co-conspirator, a comrade and a bystander — but to say much more would be to spoil the experience. It’s nice to be a ghost or voyeur or observer in VR, but I find that it’s much more compelling to be a part of the storyworld: to feel like your presence matters.

Get Kathryn Yu’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

SubscribeSubscribe

To actually initiate each VR experience, I follow the instructions to reach out and touch a tower of light in the center of each room. Sometimes I teleport onto the beam by mistake and it disappears. (Teleportation accuracy doesn’t seem to be my strong suit.) I imagine a different interface where there’s perhaps a physical button I can collide with, one with some haptic feedback. There’s also a button on my controller I can press to exit each experience once it’s started, but it doesn’t always work for me; I find myself needing to do a reset more than once. A plaque placed outside each VR piece lists its title and synopsis, but I want more information; the plaque’s presence also seems to imply a “finished” nature for each work. Maybe placing this festival, which is also a marketplace for people to pitch unfinished works, in a “museum” gives the overall event baggage that it doesn’t need. The runtime for each work also isn’t listed anywhere or displayed within the Museum. Nor can I easily find a piece’s comfort level and space requirements. I have no idea if I should be standing or sitting until I begin a particular project. I also don’t know if my small living room is going to be enough space to do what I want to do. On occasion, I bang my hand on some furniture as I reach the edge of my guardian.

Many of these exhibits would have likely done an elaborate themed build out as part of a physical festival like Tribeca; here, virtual gallery’s layout has led to a sort of sameness permeating throughout without any visual elements to draw people in from the hallway, with the exception of Minimum Mass, which has placed Lovecraftian tentacles which reach out into the main hall. Plus, the scale of each wing also makes it arduous to do a quick survey of all the exhibits. At the end of each hallway is a giant blank dark wall with some instructions written upon it; I only find out later that participants can teleport onto this wall and go to the other half of the exhibits which have been placed upon the ceiling. Hence, the missing Veer and Positron pieces were above me all along. This gravity-defying M.C. Escher-esque design cleverly doubles the number of exhibits that can be squeezed into the virtual space but seems nearly undiscoverable on one’s own. I wonder if an infinite circular 3D space or showing a ramp or some stairs leading up to the ceiling might have worked better.

This experience also marks the first time I’ve actively missed the folks who work the booths at these events: those patient angels who wipe down and sanitize every headset and controller, who make sure the headsets are charged up, who ensure that the sound is working, and watch that you don’t run into real life walls while you’re in VR. These are also the kind people who confirm that yes, it was supposed to end that abruptly, or that you should look around as much as you can during the first segment or reassure you that this isn’t scary, not really or that this experience requires only one button to use and here, it’s this one. I find myself surprised by the sheer amount of friction when getting into and out of each piece on my own; it turns out the hard working facilitators of a VR booth can really make or break the experience.

I also missed the ability to observe others as they went through an experience. Often the perspective of the current participant is displayed on an external monitor as part of an exhibit’s set up, acting as both a preview and advertisement for the experience itself; to see what choices others made or what aspects they gaze upon is enlightening in and of itself. Could there be a future iteration of this where there’s a virtual TV displaying what someone sees inside the headset? And I can’t even begin to count the number of serendipitous conversations I’ve had with someone at a VR festival simply because we had gone through the same experience one after another. The best part of any conference or festival are these hallway conversations, so perhaps that’s why these corridors feel so massive to me. I envision a virtual future where there’s hundreds of colorful blocky avatars roaming around; however, the few times I hop into the MOR, it’s rare that I encounter another soul, let alone three or four other avatars. Attending this festival this way, somehow feels isolating and strange, the opposite of what I hope is intended.

I eventually “run into” a few friends including VR journalist Kent Bye on the last day of the fest. I am grateful to spot Kent’s avatar. I teleport into his circle of other avatars and “send” a request to talk. I immediately feel as if I’m being rude, having intruded upon an existing conversation. This action happens without the benefit of making eye contact or even receiving a nod or smile or wave from across the room; in real life, I would have recognized his lanky profile or the sound of his voice from many yards away. Perhaps I would have sensed the presence of a friend through more subconscious means, the “feel” of another human right behind me. I find that I miss the quiet murmur of a crowd, the almost imperceptible change in the air as others move through it, and the tiny vibrations emanating from many people walking around at once, footsteps taken just beyond your current threshold — all things I used to take for granted.

Maybe VR will have these cues some day, but for the moment, that type of “sense information” isn’t yet available. It’s good to speak with Kent and I make the acquaintance of some other festival attendees, but I recognize his avatar’s geometric blob both as my friend but also not as my friend at the same time. I’m also struck by how long it’s been since I’ve seen Kent’s face, at least, in person.

For a long time now, it’s felt like location-based immersive experiences could maybe, just maybe, break out and start becoming mainstream, with the success of Secret Cinema, Meow Wolf, and The VOID, as well as the launch of Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge at Disneyland and Disney World. But all of this — and more — have come to a screeching halt in the wake of COVID-19. What previously felt like merely shaky ground has revealed itself to be quicksand and the formidable structures we were barreling towards now look like mirages in the distance, shimmering out of reach. Were these ivory towers of “making it” ever accessible in the first place, or, were they, like so much of modern life, merely facades, made of cleverly constructed backdrops and Hollywood sets? It’s hard to know for sure when it feels like you’re living in not only the darkest timeline, but also the most preposterous one. (Outside the USA, your perspective may differ. But I digress.)

I don’t know what’s going to become of location-based virtual reality venues and in-person festivals of immersive work in the near term: the Sundances, the Tribecas, the Venices of the VR world. These fests are where the public often gets to see an XR piece, completed or in a workable state, for the very first time. Without these showcases, a lay person might very well assume that the only thing VR is good for is creating even more shoot ’em ups and other games centered around combat. And a lot of what gets shown on the XR festival circuit is truly on the cutting edge of mixed reality, even if creators who showcase at these festivals are not guaranteed commercial success or a wider audience despite winning awards. (Sadly, distribution is still an unsolved problem.)

But still, I’m grateful I get to participate in something like this, even if I had technical difficulties and usability issues. Whichever big festival event happens next in VR, I’ll probably attend that one, too. And the following one, and the following one, until it is safe to gather once again. And I’m hopeful that post-pandemic we can find a better way to integrate the physical with the virtual, the co-located with the distributed, reaching those who can afford to travel to New York City or Austin or Park City or Lazzaretto Vecchio island as well as those who cannot. These kinds of VR events showcase the most ambitious of the wildly ambitious, with creators pushing at the boundaries of human imagination, storytelling, and technology. It would be a shame to lose them.

Hell, this kind of immersive festival needs to survive because they are the only places I’ve found for those who are creating the future to actually, physically show others what’s possible. You can take screenshots of virtual reality, you can talk about VR on podcasts, you can record video from your VR headset and share it online. But there’s no substitute for actually going through an experience and trying it for yourself: to actually be present inside someone else’s world. And putting a VR festival into VR lets us do that, for the moment.

As always, when it comes to immersive work, experiencing is believing.

Cannes XR has concluded. Learn more about the Museum of Other Realities.

NoPro is a labor of love made possible by our generous Patreon backers. Join them today!

In addition to the No Proscenium web site, our podcast, and our newsletters, you can find NoPro on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, in the Facebook community Everything Immersive, and on our Slack forum.

Office facilities provided by Thymele Arts, in Los Angeles, CA.