Lost in the Woods: ‘Sherwood & Nottingham’ (The NoPro Review)

Spy Brunch serves up an online buffet, but not every dish is a winner

The pandemic age has opened up new worlds for immersive. Companies across the globe have embraced a variety of interactive platforms — from the ubiquitous Zoom to more experimental tools like Gather — and techniques that cut across various disciplines: theatre, alternate realities, escape games, and live action role playing.

The first season of the ambitious Sherwood & Nottingham from LA’s Spy Brunch, which played out over the 2020 holiday season, gleefully embraced this Big Bang of tools.

Zoom, Twitch, Gather, a custom web site, recorded performances, live performances, and physical ephemera all were brought to bear. Yet while some of the highs were high — I count one moment in the experience as one of my highlights of 2020 (“Gail Hensworth’s Nervous Disposition”) — the overall effect created a gestalt that never quite seemed to know exactly who it was meant for.

Which doesn’t mean that there’s no future for the intended series, but that’s getting ahead of ourselves. Let’s start with what it was, which was a lot.

Urban Planning A Fictional Town

S&N is set in a fictional version of England, named Anglia, in what feels like an early 20th century timeline that happens to have the Internet — here called The Wires. The ruler is good King Richard, whose just reign has had its share of bumps. Foreign wars left psychic scars on the kingdom, and her people, most notably the King’s brother Prince John, whose wartime crimes still cast a shadow of shame on the royal house.

Sherwood. Nottingham. King Richard. Prince John.

These names either bring to mind images of Errol Flynn, Kevin Costner, or the one true Robin Hood — who is a real fox. Well, a cartoon fox anyway. There’s also the chance that you’re a major Robin Hood freak, like me, and they bring to mind Sean Connery and the ITV television series from the 80's as well. (Heaven help you if you flash on Taron Egerton. I’m just sorry for you.)

Legendary characters provide archetypal shorthand, and that’s always a solid choice for experimental work. Old stories are a narrative compass for the audience that point towards meaning even if the the tale at hand can get tangled. There’s also fodder for subversion of expectations, although that can prove the be a double edged sword.

Here the well-known characters were divided amongst the two branches of the story world, with some of them anchored in Sherwood Forrest, and others in the urban setting of Nottingham. The cast of players — full on participants paid $150 to play, whereas spectator-only tickets were available for $50 — were also divided between the city and the woods, with separate but interwoven storylines playing out along the various platforms. Luckily the majority of the platform hopping was anchored to a central web site, which streamlined the ARG aspects of the experience into something more like a constructed playground with distinct features.

A few days before launch of the online platform a small care package filled with ephemera — a “newspaper” consisting of two pages complete with a crossword and jumble puzzle, a map of the local world (Anglia, Normandy, and Aragon), along with a coaster from and brochure for Baroness Serena’s Crystal Room featuring the burlesque talents of Miss Eliza Wolfe — arrived by hand delivery.

The graphic design of the pieces was top notch, equaling the quality of work I’d encountered in mass market mystery boxes. Only here, instead of being complete in and of itself, the printed material hinted that the lore would be played out by a skilled troupe of actors. The newspaper revealed Richard to be played by Mike Merchant (Creep, Night Fever), John by Alexander Demers (The Johnny Cycle, Ebenezer), and Eliza by Katie Rediger (Safehouse ’77, Coin and Ghost), all fine talents who elevate any project they’re in.

The little packet acted as a window into the world, and a teaser that seemed to promise something like a slightly torrid, pulpy take on the backstory for the classic Robin Hood tale. In short: it got me going.

Onboarding & Idle Hands

Between the mailer and the onboarding emails, we were given a fairly clear sense of how a week in the world of S&N would work: the centerpiece would be the web site with its bulletin boards and in-character email system. Four days a week there would be events that presumably would act as tentpoles for the overarching narrative: a newscast on Wednesdays, variety performance on Thursdays, community Zoom event on Fridays, and a roleplaying session on on Saturdays in a custom forest map on the Gather platform. This last was reserved for the VIPs. The holidays meant that there were some disruptions — Thanksgiving shifted some things around — but this was generally the pattern, with Sundays through Tuesdays being off days for programming, even if the in-world comms were up and running when the production team wasn’t cranking out new content.

This structure is reminiscent of the dynamic of a long running LARP, with gametime balanced out by downtime. Indeed much of what Spy Brunch had set up structurally looked at first like a LARP. At least for participatory ticket holders. One first blush it was impressive as heck and held the promise of an ARG-style unfolding of a story, but without the FOMO panic of waiting on drops or racing around the real world to complete tasks. The design of the schedule implied when and where the stuff that mattered should be happening.

A quiz helped sort players into which part of the world — Sherwood or Nottingham — and which of the various guilds we would be assigned to. These were less like “teams” and more like the kind of character classes you might find in a game of Vampire: The Masquerade. Your guild determined your basic function in the world, and who your primary contacts were, but there were no game mechanics beyond that. So less of a character sheet LARP and more of a freeform exercise that blurred the lines between immersive theatre and heavy role-play.

Charles Mercer, Rogue Apothecary

Yet the framing screamed LARP to these old Mind’s Eye Theatre running eyes, and if a LARP abhors anything it’s a narrative vacuum. So with a couple of days of free play on the boards before the kickoff newscast I let my imagination off its leash.

I’d been given a position in what was called the Medical Mercers guild — basically, apothecaries — and was “living” in a kind of early 20th century war ravaged Europe whose England was facing a plague.This inspired me to tear a page out of Graham Greene and play my part as if I was Harry Lime, villain of The Third Man and one of Orson Welles’ most famous roles. In the film Lime is a roguish smuggler who just so happens to be ripping off vital medical supplies for his own profit. (Um, ah, spoilers for The Third Man, sorry.) Without a mandated character objective from the setting, I went about riffing on the idea of a side hustling pharmacist, making slightly wild claims on the boards and adopting a curmudgeonly persona with a penchant for crude acrostics. And thus, Charles Mercer was born.

Get Noah J Nelson’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

SubscribeSubscribe

With the first news drop the table setting of the world began, and the tone was more broadly comic than what the emphemera implied, although still shot through with a bit of melancholy. Some of this was due to placing our characters in the midst of a pandemic and under their own form of lockdown. “The Wires” were a diagetic way of explaining the need for message boards and the Gather platform, but it robbed some of the romance of being in a Robin Hood world. Our character’s lives were overlaid with our own in such a way that raw escape would never be totally possible.

The variety segments were framed around chat sessions with Baroness Serena, punctuated by performances. All of which had chat windows available for the audience to trade wits and gossip in real time. This injunction to gossip started from the first episode, and it was a bit odd to be asked for hot tea from the story’s scripted characters when we were basically newborns to this world. So I looked to the first variety performance for a burst of narrative, as Rediger is a veteran of Spy Brunch’s work and a fierce burlesque performer in her own right. But no dice. It was hot, as burlesque is meant to be, but it didn’t drive the story forward in any clear way. None of the variety segments — another scorcher from Rediger’s Wolfe, a musical act, and a stand-up telling in-world jokes — seemed to be mission critical for the overarching narrative. Perhaps there were clues that hooked into the puzzle track or winks to storylines that I wasn’t privy to baked into the form, but that initial encounter dissuaded me from seeking story there.

Instead, the variety acts seemed to become a way of marking time, or background entertainment for the realtime character chats. Given the cost of the VIP tickets, I found myself wondering more than once if the resources presumably put into paying the entertainment wouldn’t have been better allocated to more time to interact with the major non-player characters.

The main story beats showed up more readily in the Town Hall segments, puzzles woven into character interactions on the message board, and the weekly LARP sessions in Gather. Yet, for the first two weeks there was little in the way of live drama, the plot moving at a somewhat glacial pace, even as there wasn’t much time to get used to a “normal” before the world had been disrupted by the installation of Prince John as the main power in Nottingham. The plot turned, but it was difficult to calculate what it meant to the lives of a player character in the city, and lord knows what meant in the woods. While the frame looked like a game, there were no real mechanical changes to the day to day lives of the players.

What story did come out in the pre-recorded segments often felt more like exposition dumps than dramatic beats, with a notable exception of one fun cable news style exchange between John and Gail Hensworth (a fantastic Reed Sights), the Guild liaison, that proved the Prince’s temper was still a problem and featured some set deco that hinted at more going on than met the eye. It was a highpoint for the pre-recorded work, and if that kind of drama had been evident from the start, the segments would have become must see TV. More satisfying on the regular were the LARP sessions, where accidental collisions with characters could lead to improvisational riffs that the team would adroitly weave back into the narrative at large.

The thing that makes interactive storytelling work at all is when the “audience” and the “storytellers” are listening to each other. Swapping places on the fly. This is what great game masters do in role playing games and the team at Spy Brunch proved to have that capacity on more than one occasion. I tend to think of stories in terms of “offers” (blame my Johnstonian improv training), and the team reincorporated the in-character “offers” that I put on the table more than once. Yet, with the sheer scope of what they were playing with, juggling pre-recorded material and multiple platforms, it was far from the focus.

To be sure: there were so many platforms, threads, and play-styles being catered to that they structurally clashed more than once. Archival web pages that allowed for wiki-style lore dives were accessible, but also acted as spoilers for broadcasts that covered the same ground. Time that could have been spent heightening dramatic tension when all eyes were fixed on the same thing was instead spent on backstory, which players could have dug up on their own and shared with each other.

A Funny Thing Happened On The Road To The Castle

Sometimes the play style differences led to potentially awkward — or awesome — moments, depending on one’s point of view.

A late in the game confrontation with John & Marion — who had become Sheriff by this point, subverting expectations based on the legends — read at points like an attempt by players to get solutions to a puzzle while the actors stonewalled them. Were the wrong passcodes being said, or were the actors just playing their roles as doublespeaking politicians? “Charles Mercer” was having none of it, so he called them on their bullshit and injected a little drama into a conversation that had been running in circles for some minutes. Some players were visibly amused, yet I imagined— even while I played Charles to the hilt — that it might be annoying to those looking for answers they seemingly weren’t going to get.

This was the moment that really crystallized for me that with all they had built — a veritable buffet of options — the overall shape of the thing wasn’t really telling us how it wanted to be played. Which isn’t the worst thing in the world, if you can overlook the whole $150 ticket price. (Mind you, we at NoPro were comped, as is standard for review and coverage consideration, which meant I had to consciously remind myself of what the table stakes were.) Depending on what you interacted with, or what you valued, one might feel like they had gotten their money’s worth.

Yet by stretching out into so many forms, the pacing of the whole affair was off. The emotional stakes of the overarching plot never quite ratcheted up enough to be dramatically dynamic. The playspace of the town was devoid of even loose mechanics — like money or a simple barter system — that could support emergent play. Mind you, they did a good job of acknowledging player offers, but there was no systems to capitalize on them.

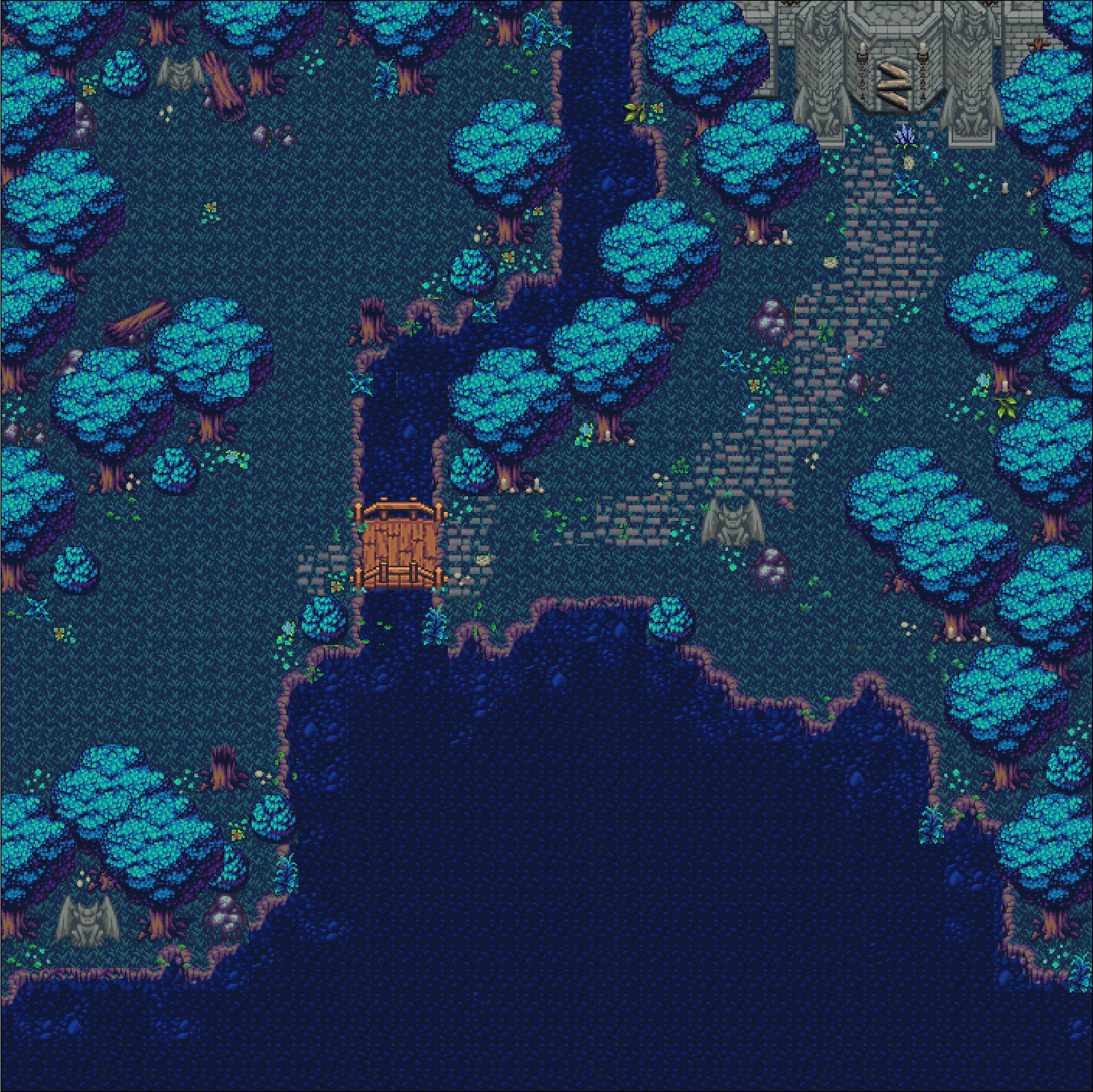

Even the Gather playspace, which was among the most accomplished and just plain pleasing pixel art maps I’ve seen on on the proximity chat service, felt underused because of all the various sub-events. A lot of effort went into the bones of this production, and so it’s frustrating that the actual moment-to-moment play often felt flat. Too often the structure, which looked like the cure for FOMO, ended up feeling like a content bucket that was filled for the sake of being filled.

That’s the last thing you want out of a Robin Hood LARP-like. And when we’re talking about a weeks-long experience with a persistent world, its better to make hard choices about what you can and can’t deliver. Even a talented team can’t be all things to all people. It’s not inconceivable that a second season of Sherwood & Nottingham could metabolize the lessons learned over the first, but the big question that the Spy Brunch team will have to answer is: what kind of audience do they want to keep making this story for?

Do they want to make a slightly linear, puzzle-centric narrative that rewards careful parsing of contextual clues? An emergent story in the manner of a live action roleplaying game, where factional strife drives the drama? A performance-centered “lean back” experience where they control the pace of the lore? Delivering well on any one of these would be more than enough, delivering on two would be a standout. But the law of diminishing returns goes into effect as the what and how gets spread out further and further.

Which is not the fate I’d like for the ambition on display here.

The first season of Sherwood & Nottingham ran from late November to mid-December of 2020. Tickets were $150 for VIP/participant and $50 for Citizen/spectator tickets. A second season is currently planned.

Discover the latest immersive events, festivals, workshops, and more at our new site EVERYTHING IMMERSIVE, new home of NoPro’s show listings.

NoPro is a labor of love made possible by our generous Patreon backers. Join them today!

In addition to the No Proscenium web site, our podcast, and our newsletters, you can find NoPro on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, in the Facebook community Everything Immersive, and on our Slack forum.