‘A Forest for the Trees’ Is the Future of Immersive (The NoPro Review)

Glenn Kaino partners with The Atlantic, Superblue, and Mastercard to glorious effect

Last month I time traveled. In downtown Los Angeles I saw the past and the future.

There was water and fire, color and darkness, music and spoken word. I was gifted new rituals. I experienced ancient wisdom.

And I met robot trees.

Inhabiting 28,000 square feet within a warehouse, A Forest for the Trees consists of interactive art, including multiple tree “performances.” Participants move through a progression of spaces and installations while retaining freedom of exploration and “agency of imagination,” as described by artist Glenn Kaino, the production’s creator and steward. It’s a fusion of culture, science, and advocacy by way of embodied, immersive storytelling.

Presented by The Atlantic and Superblue, and sponsored by Mastercard, A Forest is the result of a “conspiracy of support.” This corporate network may seem like an odd family: an institutional publication, an experiential art initiative, and a payment platform. The connective tissue is the production’s clear and resonant intentionality.

The show is an exploration of a fundamental question: Who owns our wilderness? That question is also the title of a series by The Atlantic, launched last year with an essay by David Treuer, a best-selling author from the Ojibwe Tribe. Inspired by The Atlantic’s editorial series, Kaino created a constellation of partnerships which integrates Indigenous narratives, local history, the need for individual responsibility, and the opportunity for collective action.

The Atlantic was co-founded in 1857 by philosopher and poet Ralph Waldo Emerson. Partly inspired by Emerson, naturalist and author John Muir (known as “the Father of the National Parks”) drafted lyrical missives for The Atlantic, advocating for the “preservation” of these “wildernesses.” In 1872, 15 years after the inception of The Atlantic, Yellowstone National Park was established. To date, the US has inaugurated 63 national parks comprised of tens of millions of acres.

But the lands these parks became weren’t wilderness — they had been inhabited, cultivated, and cared for by Indigenous peoples for thousands of years until violent, forced depopulation by white imperialists. Controlled burns, a Native practice, were outlawed in the early 1900s. More than a century later these natural habitats are suffering for it. Not only were Natives barred from cultural practices and serving as custodians of their homelands, and not only have these ecosystems incurred monumental damage as a result, but officials are now imploring Native Tribes to help clean up the mess.

One of the many inequities and fallacies with this tactic is that it requires sacred knowledge to be disseminated outside of Indigenous communities in order to work in tandem with the government. Orchestrated by white colonizers, America’s wilderness have undergone two eras of extraction: first the Gold Rush and then the ravaging for lumber. Kaino explained that we are currently in a third age of corrupt consumption: the sacred knowledge of America’s Indigenous peoples. A Forest spotlights this issue of “knowledge sovereignty.” Comprehensive management of the National Parks encompasses knowledge and the land itself; neither can be extricated from the other without harm.

Get Laura Hess’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

SubscribeSubscribe

Described by Treuer as “a time of historical reconsideration,” Kaino and his collaborators designed A Forest as a method to “decolonize in real time.” The show’s messaging and activism (what Kaino refers to as scholarship) are imbued in the production’s DNA. This process is a careful, foundational craft. Productions more commonly incorporate social impact as a later-stage consideration, compared to Kaino’s approach of early and concurrent consideration. All design elements of A Forest — art, show, and scholarship — are interlaced; from brainstorming to execution, discoveries for the art elements were evaluated for their effect on the show and scholarship elements, and vice versa.

Interconnectivity is a consistent theme in Kaino’s work and creative process. It appears literally and metaphorically in A Forest. He also possesses a particular affinity for magic and illusion, whether it’s the magic of the natural world or the illusion of separateness. Kaino views A Forest as a beginning, a catalyst for participants to witness and contribute to the “forest of stories,” and without that exchange the show is fractured and incomplete.

Upon entry to A Forest is a grove of black microphones. Traces of soot on the mics punctuate their charred, matchstick silhouettes. Each one has been rigged to act as a speaker, reversing their usual role and suggesting a bit of role reversal for guests. Audio volumes for these personal, tree-related tales are turned low; leaning in to hear the voices feels like the gentle prelude to a kiss.

The second phase invites participants into a story of ceremony and science. Within a darkened room, illuminated panels reveal the Karuk Tribe’s annual tradition of controlled burns and their beneficial, cascading effects.

A new ritual is next and this one particularly leverages Kaino’s gift for transforming the seemingly simple into a moment of wonder and kinship.

These three stages prime participants for A Forest’s second act: a cavernous woodland with four installations. Reclaimed remnants of redwoods border the space, encircling a well of illusion, a raked stage of fire, and animatronic trees flanking a sculpture representing an ancient Great Basin bristlecone pine (which have lived through ice ages, the rise of major religions, and the fall of great empires).

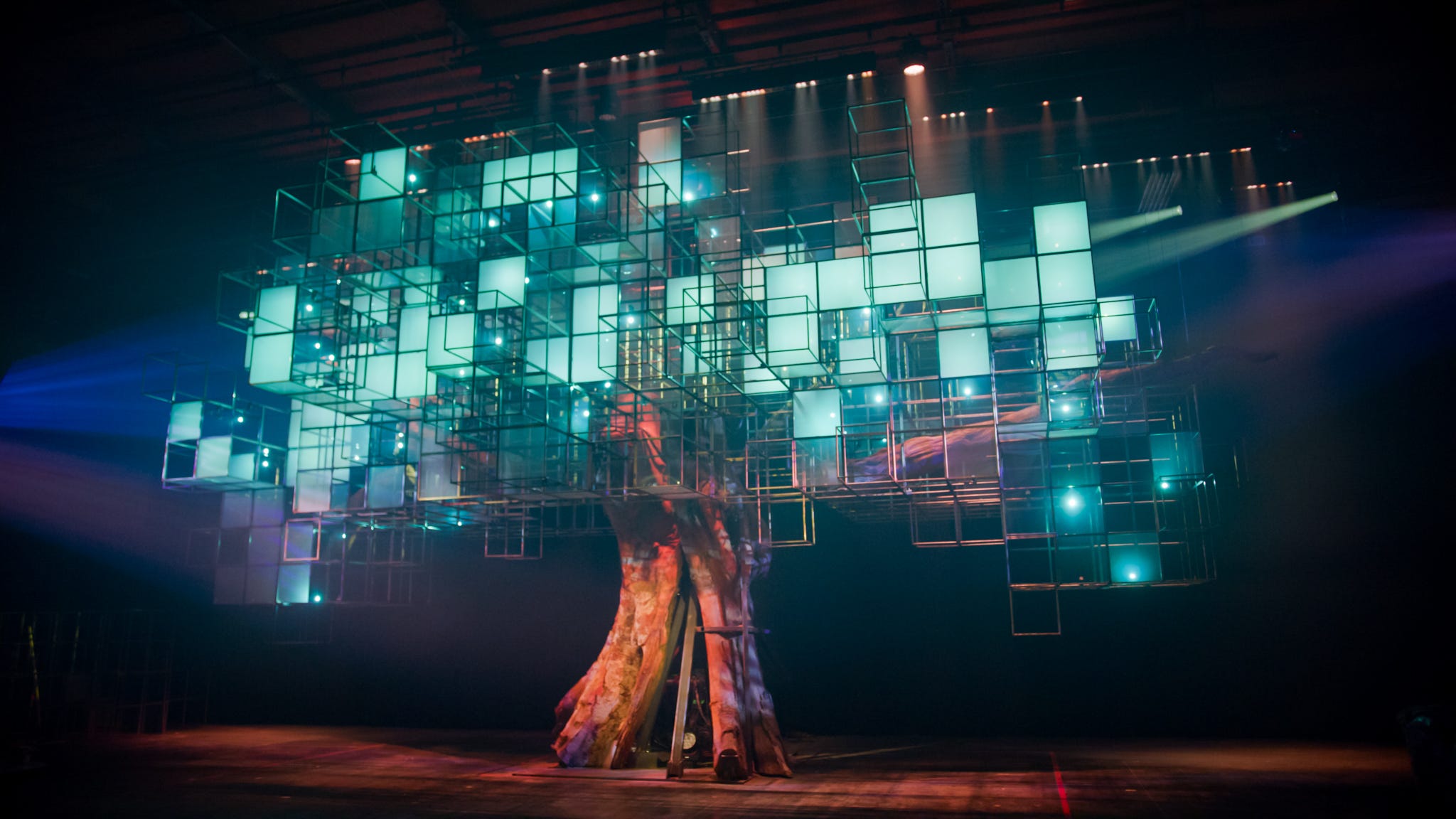

The finale is a towering fusion of the natural and manmade worlds. Resurrection reassembles the trunk of LA’s historic Olvera Street fig tree with pixelated branches of glass and steel. Felled by a storm in 2019, the Olvera fig stood for 144 years. Graduations, engagements, and weddings were commemorated under its canopy; the tree served as a kind of life officiant. Kaino describes a need to reframe our relationship to nature, to see it “as a partner, not as a provider.” And now, the Olvera fig presents itself anew, a coalition of the past and an imagined future.

I see another beginning with A Forest. Kaino said “the opportunity of art is to show pathways for things that have not yet existed.” A Forest stands as an ideal model: holistic immersive. It is participatory art fueled by inclusive and empowered collaboration, ethical and sustainable practices, and diverse institutional support, all with the singular goal of building community through empathetic action.

A Forest for the Trees presents a set past. It also offers a future full of real magic.

A Forest for the Trees runs through Thursdays — Sundays through July 10th. Tickets are $13.50– $40, with a portion of the proceeds of each ticket going to Conservation International.

Discover the latest immersive events, festivals, workshops, and more at our new site EVERYTHING IMMERSIVE, new home of NoPro’s show listings.

NoPro is a labor of love made possible by our generous Patreon backers. Join them today!

In addition to the No Proscenium website, our podcast, and our newsletters, you can find NoPro on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, in the Facebook community Everything Immersive, and on our Discord.